The Bank Job and the Death Penalty -- 1925

By David Moore - Rogers Daily News, 1980 - Now the NWA Democrat Gazette

By David Moore - Rogers Daily News, 1980 - Now the NWA Democrat Gazette

In the summer of 1925, four young bank robbers from Indiana found themselves facing the wrath of an outraged county that was sick of robberies and would not tolerate murder. They had robbed the Sulphur Springs bank on June 11, and one of them had killed banker Lou Stout.

When lawyer John W. Nance, hired by the bankers association to assist prosecutor J. S. Combs, finished with them a month later, one of the robbers became the only person condemned to death by a Benton County court in the 20th century.

John Burchfield, 28, the gang's reputed leader, Tyrus Clark, 27, Elva McDonald, 21, and Boyd Jewell, 21, broke camp on the White River east of Rogers on Thurday July 11. They got into the Ford and drove back to the road and struck out for Sulphur Springs.

The gang had robbed the Seligman train depot two days before, but the loot only amounted to $60 and the night watchmans shotgun.

Arriving in Sulphur Springs shortly before noon. Burchfield parked the car some distance from the bank. He and McDonald poked their pistols into their pants and walked to the bank.

Miss Ambercrombie, the bank's assistant cashier, saw them coming. She was warned about a month before that Oklahoma authorities supected another robbery attempt on the bank. The bank had been robbed three times before, and Miss Abercrombie was locked into the vault each time.

She left the bank and hurried over to a merchandise store operated by Lou Stout, the banks president.

Meanwhile, Marjorie Bryant, a young women from Rogers in Sulphur Springs on an outing with her family with her had parked the Nash Touring car she was driving catercorner to the bank.

Entering the bank, Burchfield and McDonald drew their weapons and ordered cashier Storm Whaley to hand over the money. Whaley and another customer were then locked in the vault, and the bandits walked back onto the street.

Down the street stood Strout and his son armed with shot guns ordered the bandits to halt. Firing erupted from the Ford. Burchfield and McDonald shot simultaneously. Stout fired five times before he was struck in the belly. Another son rushed out of the store, grabbing his father's gun and began shooting.

When lawyer John W. Nance, hired by the bankers association to assist prosecutor J. S. Combs, finished with them a month later, one of the robbers became the only person condemned to death by a Benton County court in the 20th century.

John Burchfield, 28, the gang's reputed leader, Tyrus Clark, 27, Elva McDonald, 21, and Boyd Jewell, 21, broke camp on the White River east of Rogers on Thurday July 11. They got into the Ford and drove back to the road and struck out for Sulphur Springs.

The gang had robbed the Seligman train depot two days before, but the loot only amounted to $60 and the night watchmans shotgun.

Arriving in Sulphur Springs shortly before noon. Burchfield parked the car some distance from the bank. He and McDonald poked their pistols into their pants and walked to the bank.

Miss Ambercrombie, the bank's assistant cashier, saw them coming. She was warned about a month before that Oklahoma authorities supected another robbery attempt on the bank. The bank had been robbed three times before, and Miss Abercrombie was locked into the vault each time.

She left the bank and hurried over to a merchandise store operated by Lou Stout, the banks president.

Meanwhile, Marjorie Bryant, a young women from Rogers in Sulphur Springs on an outing with her family with her had parked the Nash Touring car she was driving catercorner to the bank.

Entering the bank, Burchfield and McDonald drew their weapons and ordered cashier Storm Whaley to hand over the money. Whaley and another customer were then locked in the vault, and the bandits walked back onto the street.

Down the street stood Strout and his son armed with shot guns ordered the bandits to halt. Firing erupted from the Ford. Burchfield and McDonald shot simultaneously. Stout fired five times before he was struck in the belly. Another son rushed out of the store, grabbing his father's gun and began shooting.

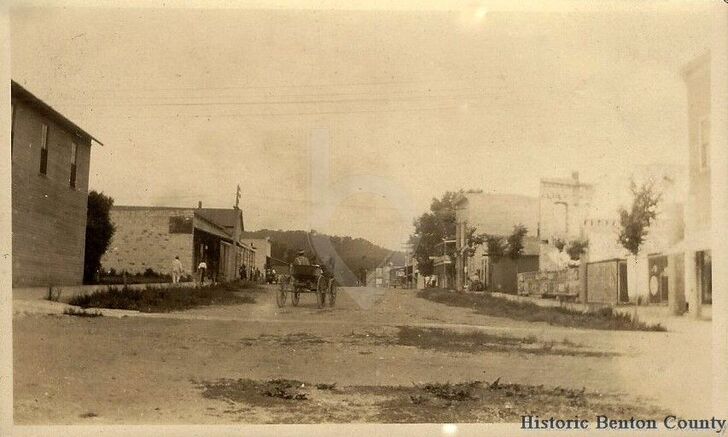

This is an image of Sulphur Springs around the time the Sulphur Springs robbery would have occurred

A block away Marjorie Bryant heard the gunfire. Her sister, Mrs. Ralph Johnson, said, "It's a holdup!" "They're just shooting at a dog," said another. A bullet whined over Marjorie's shoulder and slapped into the car. "They're killing a man!" Mrs. Johnson screamed. Marjorie shoved the Nash in gear and raced out of town.

The bandits ran for the Ford. Burchfield jumped inside. McDonald jumped on the running board and hung on. Citizens, alerted by the gunfire, jumped into their cars and gave chase. The bandits missed a turn and wrecked into a tree. Clark and McDonald fled on foot into the woods. Jewell and Burchfield staggered out of the car and were subdued.

Sheriff Joe Gailey fromed a posse and gave pursuit. They overran the two remaining outlaws near Maysville at dawn. They escaped, but not before two members of the posse were shot.

Gailey finally caught up with Clark on Sunday near Catoosa, Okla., where he was hiding in a thicket. McDonald was captured by a farmer the following day while sleeping under some brush. The farmer had probably heard of the $1,000 reward offered jointly by the Benton County and state bankers associations.

A special session of circuit court was called on June 18 by Judge W. A. Dickson. A grand jury convened on June 29 and returned indictments against the four men the next day charging them with robbing the bank of $900, burglrizing the bank, and "murdering one Lou Stout by shooting him on the body with a certain gun loaded with gunpowder and leaden balls." Clark pulled the trigger, the indictment said.

The bandits ran for the Ford. Burchfield jumped inside. McDonald jumped on the running board and hung on. Citizens, alerted by the gunfire, jumped into their cars and gave chase. The bandits missed a turn and wrecked into a tree. Clark and McDonald fled on foot into the woods. Jewell and Burchfield staggered out of the car and were subdued.

Sheriff Joe Gailey fromed a posse and gave pursuit. They overran the two remaining outlaws near Maysville at dawn. They escaped, but not before two members of the posse were shot.

Gailey finally caught up with Clark on Sunday near Catoosa, Okla., where he was hiding in a thicket. McDonald was captured by a farmer the following day while sleeping under some brush. The farmer had probably heard of the $1,000 reward offered jointly by the Benton County and state bankers associations.

A special session of circuit court was called on June 18 by Judge W. A. Dickson. A grand jury convened on June 29 and returned indictments against the four men the next day charging them with robbing the bank of $900, burglrizing the bank, and "murdering one Lou Stout by shooting him on the body with a certain gun loaded with gunpowder and leaden balls." Clark pulled the trigger, the indictment said.

Main Street -Suphur Springs (Cir. 1920's)

The men were arraigned; they retained local attorneys and trials were set. The Rogers Daily Post editorialized on its front page, blaming the prison parole system "which enables and allows practical freedom to such criminals" for Stout's death, even though the paper's sporadic and incontistant reporting stated that Burchfield had escaped from the Arkansas Penitentiary in 1920 and Clark had recently escaped from an Indiana jail.

Rogers attorney Jeff Duty recalled that his father, John, was originally hired to defend Burchfield. However, Duty remembered, as he sat on the porch one day a big, black car pulled into the driveway at his father's home. John Burchfield's father, a Madison county resident, got out, leaving three other men inside. John Duty came out to discuss the case, telling Burchfield not to worry. "I'm not worried, John's not going to trial," Burchfield said.

"What do you mean?" Duty asked. In response, Burchfield pulled back his coat, exposing a gun. "I'm going to kill the sheriff," Burchfield said. He led Duty to the car and showed him that the other men were armed as well.

Duty said his father returned Burchfield's money and told him to find another lawyer. The sheriff was informed of what Burchfield said.

A few days later, when Burchfield was taken from the jail to the courthouse, Duty said a wall of armed deputies formed a sort of tunnel. In the center, the sheriff and the bandit walked surrounded by a ring of deputies. Burchfield told chief deputy Edgar Fields, "You've got the army out today."

"That right, John, there won't be any shooting today," Fields said.

McDonald was tried first. 137 jurors were questioned before attorneys found 12 to try the case. 56 were opposed to capital punishment and 28 had formed opinions of McDonald's guilt or innocence. In testimony, McDonald said he did not shoot. Judge Dickson reminded the jury it did not matter who actually fired the shot that killed Stout because an accomplice is just as guilty. Various witnesses declared the first shot came from the car in which Clark and Jewell sat. Despite an impassioned plea for the death penalty by Combs and Nance, the jury recommended life imprisonment.

Burchfield's trial was continued when some of his subpoenaed witnesses did not show up. Jewell agreed to a plea bargain. In return for testifying on the state's behalf, he would plead guilty to second degree murder, robbery and burglary.

Despite the fruitless attempts of Clark's attorney, W. H. Spencer of Bentonville, to get a change of venue, his trial began July 14. Spencer, Combs and Nance questioned 107 prospects before getting a jury. Judge Dickson overruled a flurry of motions from Spencer and entered a not guilty plea for Clark who refused to speak. The jury was sequestered for the night and testimony began the next day.

Again the prosecution presented witnesses, including Stout's widow, who said the first shot came from the car. Jewell testified that the gang had agreed he would drive and Clark would handle the guns. Clark claimed that he did not fire and that he was to drive if Burchfield decided not to. He said he received three wounds and was afraid to surrender after the car wrecked because of the "mob" pursuing them.

The jury was sequestered for the night again and began deliberations the next morning. It returned into court and the foreman asked Judge Dickson what Clark's sentence would be if the jury did not recommend one. Dickson told them the law required him to sentence Clark to death unless they recommended leniency.

The jury returned shortly and found Clark guilty of first degree murder. The Rogers Daily Post trumpeted, "Probably no trial has created greater interest in the county, many citizens having the belief that the results of this trial will impress upon other outlaws that Northwest Arkansas is not a good place to plunder or that it is easy picking."

Dickson postponed sentencing Clark until after the other two men were sentenced. He accepted Comb's recommendation to sentence Jewell to 21 years for second degree murder, 21 years for robbery, and seven years for burglary, and seven years for burglary, all to run consecutively.

Despite a type of insanity defense by Burchfield's attorney, Wythe Walker of Fayetteville, and tears from two women who both claimed to be his wife, Burchfield, who claimed he drove the car from the robbery scene and did not shoot, was convicted on July 18 and sentenced to life imprisonment by the jury. Walker brought on the witness stand a physician who vouched that Burchfield had a depression in his skull caused by his being struck by an iron bar when he was nine. This pressed on his brain and caused the bandit to "be the reluctant victim of wicked influence ever since," Walker told the court.

On July 20, Clark was brought before the bench. Dickson said, "The proof was conclusive in your case and the jury trying you were fully warranted in finding that it was you struck the fatal blow. It was you that kiiled Lou Stout outright, and no doubt this influenced the jury trying you and has differentiated the punishment although the legal guilt was the same and identical.

"By and from the testimony of yourself and your confederates in this crime, you calmy and deliberately premeditated and planned an expedition of robbery, larceny and burglary into the peaceful county of Benton. You came with instructions of death in your hands and murder in your heart, if an honest citizen opposed your plans.

"The laws of human society decree that you expiate your crime with your life. The court has no discretion as to punishment and must perform the painful duty. It is therefore considered, ordered and adjudged by the court upon the verdict of the jury herein: That you, Tyrus Clark, be put to death in the manner provided by law, to wit: by causing a current of electricity of sufficient intensity to cause death to be passed through your body until you are dead."

Spencer filed a detailed motion for a new trail that Dickson overruled. Spencer then appealed to the state Supreme Court and lost.

Clark continued to maintain his innocence. He told a reporter that Jewell, who had named Clark as the killer, had lied. Clark said the hammer on his shotgun failed and it would not shoot.

In November, Jewell confessed to the lie, and admitted that he not Clark had really shot Stout.

Efforts by horrified Benton Countians to commute Clark's sentence failed. More than 4,000 persons signed a petition to the govenor, including the nine of the jurors who convicted Clark. It was taken to Little Rock by Bentonville attorney Vol Lindsey who, along with a number of clergymen, pleaded for Clark's life. Gov. Terral, who had taken a stand against the early parole of criminials and, it was rumored, was under tremendous pressure by the state banks association, denied the petition.

Clark was executed on Jan. 8, 1926, the only person in the Twentieth Century ever sentenced to death by a Benton County jury [at that time]. As he calmly entered the death chamber, his last words were, "God help them for all this."

Three other persons were condemned by Benton County juries. Two were Indians, hung in 1844 and 1853, accused of killing other Indians. The third was a white man named Cornelius Hammon. His hanging on Jan. 14, 1876 attacted a crowd area newspapers estimated at 10,000. Hammon was taken riding astride his coffin in a horse-drawn wagon to a scaffold erected south of Bentonville. His last words before the trap was sprung were, "You are hanging the wrong man."

Rogers attorney Jeff Duty recalled that his father, John, was originally hired to defend Burchfield. However, Duty remembered, as he sat on the porch one day a big, black car pulled into the driveway at his father's home. John Burchfield's father, a Madison county resident, got out, leaving three other men inside. John Duty came out to discuss the case, telling Burchfield not to worry. "I'm not worried, John's not going to trial," Burchfield said.

"What do you mean?" Duty asked. In response, Burchfield pulled back his coat, exposing a gun. "I'm going to kill the sheriff," Burchfield said. He led Duty to the car and showed him that the other men were armed as well.

Duty said his father returned Burchfield's money and told him to find another lawyer. The sheriff was informed of what Burchfield said.

A few days later, when Burchfield was taken from the jail to the courthouse, Duty said a wall of armed deputies formed a sort of tunnel. In the center, the sheriff and the bandit walked surrounded by a ring of deputies. Burchfield told chief deputy Edgar Fields, "You've got the army out today."

"That right, John, there won't be any shooting today," Fields said.

McDonald was tried first. 137 jurors were questioned before attorneys found 12 to try the case. 56 were opposed to capital punishment and 28 had formed opinions of McDonald's guilt or innocence. In testimony, McDonald said he did not shoot. Judge Dickson reminded the jury it did not matter who actually fired the shot that killed Stout because an accomplice is just as guilty. Various witnesses declared the first shot came from the car in which Clark and Jewell sat. Despite an impassioned plea for the death penalty by Combs and Nance, the jury recommended life imprisonment.

Burchfield's trial was continued when some of his subpoenaed witnesses did not show up. Jewell agreed to a plea bargain. In return for testifying on the state's behalf, he would plead guilty to second degree murder, robbery and burglary.

Despite the fruitless attempts of Clark's attorney, W. H. Spencer of Bentonville, to get a change of venue, his trial began July 14. Spencer, Combs and Nance questioned 107 prospects before getting a jury. Judge Dickson overruled a flurry of motions from Spencer and entered a not guilty plea for Clark who refused to speak. The jury was sequestered for the night and testimony began the next day.

Again the prosecution presented witnesses, including Stout's widow, who said the first shot came from the car. Jewell testified that the gang had agreed he would drive and Clark would handle the guns. Clark claimed that he did not fire and that he was to drive if Burchfield decided not to. He said he received three wounds and was afraid to surrender after the car wrecked because of the "mob" pursuing them.

The jury was sequestered for the night again and began deliberations the next morning. It returned into court and the foreman asked Judge Dickson what Clark's sentence would be if the jury did not recommend one. Dickson told them the law required him to sentence Clark to death unless they recommended leniency.

The jury returned shortly and found Clark guilty of first degree murder. The Rogers Daily Post trumpeted, "Probably no trial has created greater interest in the county, many citizens having the belief that the results of this trial will impress upon other outlaws that Northwest Arkansas is not a good place to plunder or that it is easy picking."

Dickson postponed sentencing Clark until after the other two men were sentenced. He accepted Comb's recommendation to sentence Jewell to 21 years for second degree murder, 21 years for robbery, and seven years for burglary, and seven years for burglary, all to run consecutively.

Despite a type of insanity defense by Burchfield's attorney, Wythe Walker of Fayetteville, and tears from two women who both claimed to be his wife, Burchfield, who claimed he drove the car from the robbery scene and did not shoot, was convicted on July 18 and sentenced to life imprisonment by the jury. Walker brought on the witness stand a physician who vouched that Burchfield had a depression in his skull caused by his being struck by an iron bar when he was nine. This pressed on his brain and caused the bandit to "be the reluctant victim of wicked influence ever since," Walker told the court.

On July 20, Clark was brought before the bench. Dickson said, "The proof was conclusive in your case and the jury trying you were fully warranted in finding that it was you struck the fatal blow. It was you that kiiled Lou Stout outright, and no doubt this influenced the jury trying you and has differentiated the punishment although the legal guilt was the same and identical.

"By and from the testimony of yourself and your confederates in this crime, you calmy and deliberately premeditated and planned an expedition of robbery, larceny and burglary into the peaceful county of Benton. You came with instructions of death in your hands and murder in your heart, if an honest citizen opposed your plans.

"The laws of human society decree that you expiate your crime with your life. The court has no discretion as to punishment and must perform the painful duty. It is therefore considered, ordered and adjudged by the court upon the verdict of the jury herein: That you, Tyrus Clark, be put to death in the manner provided by law, to wit: by causing a current of electricity of sufficient intensity to cause death to be passed through your body until you are dead."

Spencer filed a detailed motion for a new trail that Dickson overruled. Spencer then appealed to the state Supreme Court and lost.

Clark continued to maintain his innocence. He told a reporter that Jewell, who had named Clark as the killer, had lied. Clark said the hammer on his shotgun failed and it would not shoot.

In November, Jewell confessed to the lie, and admitted that he not Clark had really shot Stout.

Efforts by horrified Benton Countians to commute Clark's sentence failed. More than 4,000 persons signed a petition to the govenor, including the nine of the jurors who convicted Clark. It was taken to Little Rock by Bentonville attorney Vol Lindsey who, along with a number of clergymen, pleaded for Clark's life. Gov. Terral, who had taken a stand against the early parole of criminials and, it was rumored, was under tremendous pressure by the state banks association, denied the petition.

Clark was executed on Jan. 8, 1926, the only person in the Twentieth Century ever sentenced to death by a Benton County jury [at that time]. As he calmly entered the death chamber, his last words were, "God help them for all this."

Three other persons were condemned by Benton County juries. Two were Indians, hung in 1844 and 1853, accused of killing other Indians. The third was a white man named Cornelius Hammon. His hanging on Jan. 14, 1876 attacted a crowd area newspapers estimated at 10,000. Hammon was taken riding astride his coffin in a horse-drawn wagon to a scaffold erected south of Bentonville. His last words before the trap was sprung were, "You are hanging the wrong man."