Beaver Lake Has Sparked New Life At Historic Monte Ne

From the Rogers Daily News - Jauary 29, 1967 - Now the NWA Democrat Gazette

From the Rogers Daily News - Jauary 29, 1967 - Now the NWA Democrat Gazette

Transportation killed Monte Ne - railroads were the main way for the finer folks to travel, but cars took over and today the economy of the world is growing, allowing more people a chance to obtain fast transportation. Instead of spending several days traveling, as in the past, a short few hours will put you at the new Monte Ne.

And, when you arrive, summer homes, picnic areas, boat ramps, trailer lots and many other facilities are at your disposal. More than 255 lots were sold last year.

The following story delves into the life of the man responsible for putting Monte Ne "on the map". His name was "Coin Harvey" - a man who established a political group that became known throughout the nation, and a man that legend refuses to discard.

And, when you arrive, summer homes, picnic areas, boat ramps, trailer lots and many other facilities are at your disposal. More than 255 lots were sold last year.

The following story delves into the life of the man responsible for putting Monte Ne "on the map". His name was "Coin Harvey" - a man who established a political group that became known throughout the nation, and a man that legend refuses to discard.

The Story of "Coin" Harvey

Not too long ago a political group was hatched in the Ozarks - at Benton county's Monte Ne - and a ticket put on the ballot which received votes from every state in the Union. It happened only a few years ago. The man who ran on the Arkansas-spawned ticket only won a small percentage of the votes. but he made a splash over the nation just the same.

He was Coin Harvey, the Sage of Monte Ne, a man who made and lost a fortune and accomplished and failed in more projects than any hundred ordinary men. He was the kind of individual around whom legends grow as surely as the sun shines and the rain falls.

But back to the subject of the "third party." The fledgling organization, which sincerely hoped to put Harvey in the White House in 1933, was named the Liberty Party. Its catch phrase was "Prosperity in Ninety Days." The official newspaper, the Libery Bell, edited by Harvey, called for a "Second Declaration of Independence" and boldly stated seven resolutions from the party platform which it flatly called the remedy for all that ailed the sickly economic life of the time.

He was Coin Harvey, the Sage of Monte Ne, a man who made and lost a fortune and accomplished and failed in more projects than any hundred ordinary men. He was the kind of individual around whom legends grow as surely as the sun shines and the rain falls.

But back to the subject of the "third party." The fledgling organization, which sincerely hoped to put Harvey in the White House in 1933, was named the Liberty Party. Its catch phrase was "Prosperity in Ninety Days." The official newspaper, the Libery Bell, edited by Harvey, called for a "Second Declaration of Independence" and boldly stated seven resolutions from the party platform which it flatly called the remedy for all that ailed the sickly economic life of the time.

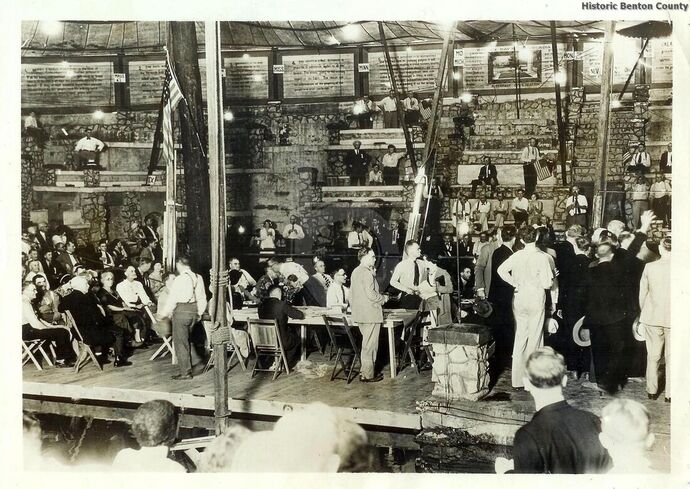

The new political party was started to save civilization. The strangest of political conventions convened in the shadow of William H. "Coin" Harvey's pyramid at Monte Ne, Ark.

When the time for the Liberty Party's convention rolled around, railroads all over the country slapped on excursion rates to the backwoods village of Monte Ne. At Rogers elaborate plans were made to take care of the great throng of delegates and visitors - 10,000 were expected - which would overflow the tiny neighboring community. When a heavy downpour washed out the road between the towns, Rogers businessmen got jittery when they pictured thousands of motorists stalled, unable to get to the convention site, and ranting about Benton county roads. A grading crew was put on the job and got the road back in shape in record time. Then all Northwest Arkansas settled down to experience the headaches - and the good publicity - of a national political conclave.

But when the long awaited convention was finally called to order at the amphitheatre - which was about all that had been built of Harvey's world-famous pyramid project - the number present was disappointing to say the least. When the roll was called there were only 786 delegates on hand. But they stood and cheered loudly as the 80-year-old Harvey faced the loudspeaker mikes which were to carry his voice out over the crowd, the amphitheater and the treeshadowed lagoon nearby.

There surely never was another political convention held in such a clean and idyllic spot. There was no chance for smoke filled rooms here. Erect, defiant and at the same time strangely impersonal, Harvey pledged the good fight for the ideals of the party - ideals which really were his own ideals as the party was his own creation.

The delegates nominated the aged Coin Harvey for the nation's highest office and then drifted back to their homes in 25 states. Remaining at Monte Ne, which was more than ever now one of the most publicized villages in the world, Harvey and his associates got busy pushing the campaign. Along with his secretary-wife and C. W. Henninger, party chairman, he settled down to some good old-fashioned journalistic tom-tom beating in the pages of The Liberty Bell. This paper, mailed throughout the United States, became the Bible of the Harvey followers. The whole Liberty Party campaign was waged with the fervor of red-hot evangelism.

But in November the mass movement of voters to Governor Roosevelt's standard must have stamped a greart many good Liberty Party people into the Democratic camp. The Liberty Party became only an exotic memory to most as the New Deal dance began.

But when the long awaited convention was finally called to order at the amphitheatre - which was about all that had been built of Harvey's world-famous pyramid project - the number present was disappointing to say the least. When the roll was called there were only 786 delegates on hand. But they stood and cheered loudly as the 80-year-old Harvey faced the loudspeaker mikes which were to carry his voice out over the crowd, the amphitheater and the treeshadowed lagoon nearby.

There surely never was another political convention held in such a clean and idyllic spot. There was no chance for smoke filled rooms here. Erect, defiant and at the same time strangely impersonal, Harvey pledged the good fight for the ideals of the party - ideals which really were his own ideals as the party was his own creation.

The delegates nominated the aged Coin Harvey for the nation's highest office and then drifted back to their homes in 25 states. Remaining at Monte Ne, which was more than ever now one of the most publicized villages in the world, Harvey and his associates got busy pushing the campaign. Along with his secretary-wife and C. W. Henninger, party chairman, he settled down to some good old-fashioned journalistic tom-tom beating in the pages of The Liberty Bell. This paper, mailed throughout the United States, became the Bible of the Harvey followers. The whole Liberty Party campaign was waged with the fervor of red-hot evangelism.

But in November the mass movement of voters to Governor Roosevelt's standard must have stamped a greart many good Liberty Party people into the Democratic camp. The Liberty Party became only an exotic memory to most as the New Deal dance began.

Coin Harvey and some of the Liberty Party officials at the convention at Monte Ne

William Hope Harvey was born in Buffalo, W. V., in 1851. Educated at Buffalo Academy and Marshall College in his home state, he became a school teacher at 16, an age when most boys were still digging fishworms. Before he was even old enough to vote he was quoting Blackstone as a member of the bar. He practiced in Cleveland and Chicago and while in the Windy City represented the milllionaire Snell for a number of years before that wealthy Chicagoan was murdered. This experience must have strongly impressed young Harvey, for he carried a life-long mistrust of the effects of great wealth.

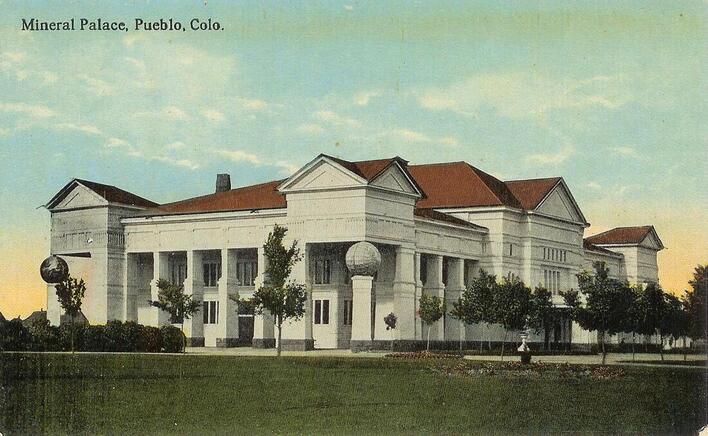

In 1884 Harvey was in Colorado, where he opened real estate offices in Denver and Pueblo. While living in the West he must have absorbed the sense of the spectacular which Westerners develop from living in a magnificent environment, for everything he was attempting from this time was on the dramatic side. He became a sort of Cecil DeMille, minus the technicolor and shapely girls, of course. In 1889 he whipped together enough contributions to finance a great palace of minerals at Pueblo, where the products of Colorado's mines were dramatized in exciting exhibits. One exhibit was never forgotten by those who visited the hall. It was gigantic statue of King Cole, carved by a Chicago sculptor from a solid piece of coal weighing 11,000 pounds. His fame as a promoter of spectacles reached Ogden, Ut., where he was invited to stage a Mardi Gras. He accepted and put on such a lively event that thousands of visitors swamped the city and were so impressed that many of them stayed as permanent residents.

In 1884 Harvey was in Colorado, where he opened real estate offices in Denver and Pueblo. While living in the West he must have absorbed the sense of the spectacular which Westerners develop from living in a magnificent environment, for everything he was attempting from this time was on the dramatic side. He became a sort of Cecil DeMille, minus the technicolor and shapely girls, of course. In 1889 he whipped together enough contributions to finance a great palace of minerals at Pueblo, where the products of Colorado's mines were dramatized in exciting exhibits. One exhibit was never forgotten by those who visited the hall. It was gigantic statue of King Cole, carved by a Chicago sculptor from a solid piece of coal weighing 11,000 pounds. His fame as a promoter of spectacles reached Ogden, Ut., where he was invited to stage a Mardi Gras. He accepted and put on such a lively event that thousands of visitors swamped the city and were so impressed that many of them stayed as permanent residents.

This is a postcard of the Mineral Palace in Pueblo, Colorado that Harvey had a major part in building

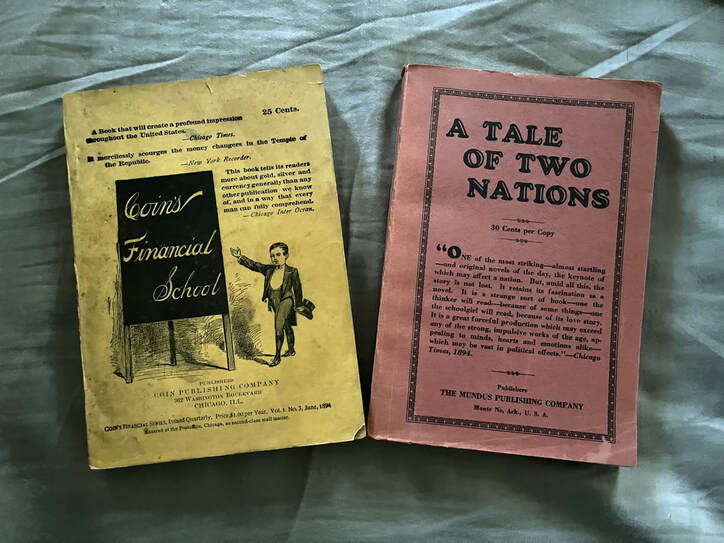

Harvey's restless energies took him back to Chicago in 1893. Always a lover of a good fight, he got in up to his neck in the struggle then raging over the free coinage of silver. He brought out a book called "Coin's Financial School," in which an eight-year-old boy named Coin completely routed the top financial wizards and economists of the day in a debate on the money question. Harvey used the youthful character to emphasize that even a school boy could understand that his (Harvey's) ideas on currency reform were sounder than the philosopy of capitalism at that time. The book caught on. A million copies were sold to set a world's record in the publishing business. However seriously they took the ideas, people fought to get a copy as strenuously as their grandchildren were to fight to get "Forever Amber." In those days perhaps sex found sublimation in economics and politics. During the same year Harvey wrote another best seller, "A Tale of Two Nations." It was a novel which pictured English money lords trying to wreck the American financial system by bribing dishonest congressmen into demonetizing silver and wrecking our international trade to the good of John Bull. One-half million copies of this great best seller were sold the first year.

Then came the hot campaign year of 1896, the year that saw William Jennings Bryan, nominated by the Democrats, make the "cross of gold" speech which cinched him as the alltime Oscar-winner among convention orators. Harvey was Bryan's advisor and close friend as well as chairman of the party's Ways and Means Committee. Bryan's defeat was upsetting to Harvey but he kept on punching against gold until his own party snubbed him and decided to scuttle the money agitation once and for all. Harvey went into a rage and resigned his position. In fact, he decided to give United States civilization up as a bad deal and go live as a hermit in a remote place.

That is why Coin Harvey came to the Ozark mountains of Arkansas.

The spot he selected for "retirement" was a tiny hamlet of Silver Springs, a few miles southeast of Rogers. He did forget politics but couldn't smother his inherent need to create something. The setting of the hills and cool sparkling springs was a natural site for a resort. He saw the chance to develop a watering place in the Ozarks where people could boil out the poisonous effects of voting the Republican ticket and defending the gold standard! He had the money to get it under way; it was rumored that he had made almost a million dollars from the sales of his books. His first move was to buy 320 acres surrounding the springs. The land was laid off into streets, drives and parks. Then he searched for a name for the new town. He found it in the Union of a Latin word with an Omaha Indian word - Monte Ne - Mountaun Water.

That is why Coin Harvey came to the Ozark mountains of Arkansas.

The spot he selected for "retirement" was a tiny hamlet of Silver Springs, a few miles southeast of Rogers. He did forget politics but couldn't smother his inherent need to create something. The setting of the hills and cool sparkling springs was a natural site for a resort. He saw the chance to develop a watering place in the Ozarks where people could boil out the poisonous effects of voting the Republican ticket and defending the gold standard! He had the money to get it under way; it was rumored that he had made almost a million dollars from the sales of his books. His first move was to buy 320 acres surrounding the springs. The land was laid off into streets, drives and parks. Then he searched for a name for the new town. He found it in the Union of a Latin word with an Omaha Indian word - Monte Ne - Mountaun Water.

This was known as Big Spring. Later the amphitheater would be built around this spring.

In 1902 gangs of hillmen started building Harvey's private railroad to Harvey's private town. When the rails had been laid, Harvey bought a complete train, engine (an ancient type with a bulbous smokestack), coal car, coach and caboose.

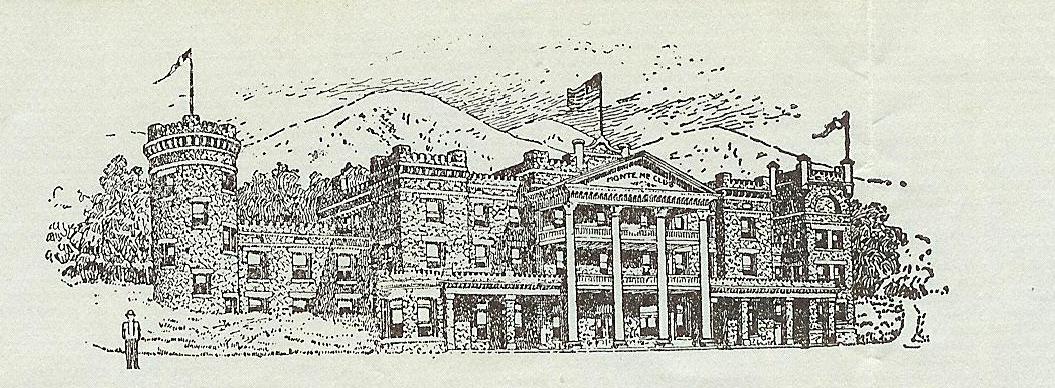

Harvey organized the Club House Hotel and Cottage Company in 1904. The company built what were probably the two largest log hotels in the world. The larger building, called Missouri Row, was 305 feet long and was built of 8,000 hewn logs, held together by 14,000 cubic feet of concrete. The other, Oklahoma Row, was almost as large. But that wasn't all. Five such buildings were planned and one story was actually built for the main club house, a building which would have been as palatial as a Roman imperial villa. This structure was to have been three stories of stone and concrete, spacious halls and parlors, and one room in which there would be an 18-foot waterfall over stone set in concrete. At each end of the building were to be 80-foot towers.

Harvey organized the Club House Hotel and Cottage Company in 1904. The company built what were probably the two largest log hotels in the world. The larger building, called Missouri Row, was 305 feet long and was built of 8,000 hewn logs, held together by 14,000 cubic feet of concrete. The other, Oklahoma Row, was almost as large. But that wasn't all. Five such buildings were planned and one story was actually built for the main club house, a building which would have been as palatial as a Roman imperial villa. This structure was to have been three stories of stone and concrete, spacious halls and parlors, and one room in which there would be an 18-foot waterfall over stone set in concrete. At each end of the building were to be 80-foot towers.

This is an image of what the Club House Hotel was supposed to look like when it was completed. This building was being worked on when Havey demanded the workers work longer hours with less pay. Many of the workers quit. There was no additional work done on this building after that. At that time he concentrated on finishing the other hotels.

When the first hotels were finished, the clients began to arrive. At the start they were families of the stockholders who were given a 25 per cent cut on rates, but later people came from all parts of the country. It was the flush time of the Edwardian Era. The extravagantly romantic ideas of this period, just before the rude shock of World War I, were in full swing. Monte Ne was a Never-Never Land such as will not be seen again in Arkansas.

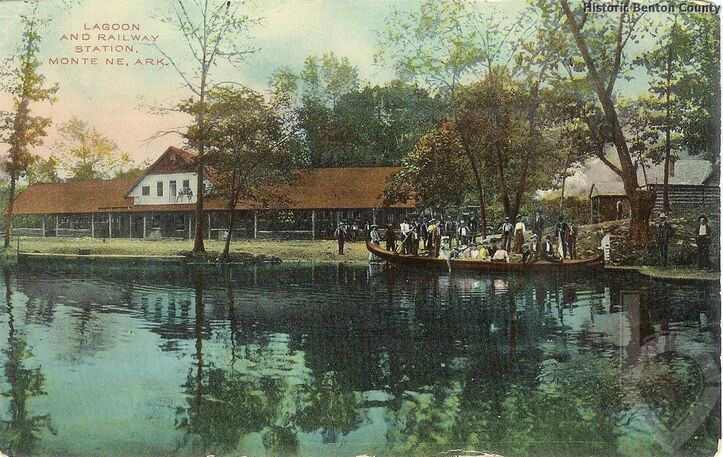

Excursions were run from many states to Lowell, where the merrymakers clambered aboard the "Monte Ne Express" for the short, jostling ride through steep, moss-covered ravines, under a canopy of wild forest. When they arrived at the attractive log station at the resort, flower decked gondolas lay waiting for them in the nearby lagoon. When the gondoliers paddled away with their cargo of carefree guests, they sang lustily in the tradition of old Venice. The watery route, leading to the dock in front of the main hotel, was half a mile long and passed under graceful stone arches and past deep shade of mysterious inlets where cicadas and frogs held jam sessions.

Excursions were run from many states to Lowell, where the merrymakers clambered aboard the "Monte Ne Express" for the short, jostling ride through steep, moss-covered ravines, under a canopy of wild forest. When they arrived at the attractive log station at the resort, flower decked gondolas lay waiting for them in the nearby lagoon. When the gondoliers paddled away with their cargo of carefree guests, they sang lustily in the tradition of old Venice. The watery route, leading to the dock in front of the main hotel, was half a mile long and passed under graceful stone arches and past deep shade of mysterious inlets where cicadas and frogs held jam sessions.

Monte Ne was the only place in the U.S. where a gondola would pick you up from the train depot and take you to your hotel.

Mr. Harvey brought over gondoliers from Italy to train the people to operate the gondolas.

Contrary to this article, not all the gondoliers sang as they transported their passengers.

Mr. Harvey brought over gondoliers from Italy to train the people to operate the gondolas.

Contrary to this article, not all the gondoliers sang as they transported their passengers.

There was no puritanism at Monte Ne. Balls were held at the rustic wooden auditorium with music furnished by imported orchestra that knew ragtime as well as waltz. There was an enclosed swimming pool-called a plunge bath then - which was the first one in this section. And the first golf course in the area was here. (The sight of gentlemen players in knickers must have started all the hounds in the hills baying). All this, along with the clean air and lovely contoured hills had its impression on the visitor. One young Ohio woman, writing from England to a friend, remarked that on a tour of England she found no place as beautiful as Monte Ne.

On the night of February 11, 1936, Coin Harvey, the most fabulous man who ever lived in Arkansas, died. Perhaps he died with a broken heart, no one knows but his wife who was with him. She was the former Mae Leake of Springfield, Mo., who for a quarter of a century had been his secretary and close friend. They were married in 1929, when Harvey finally got a divorce from his first wife after a separation of 30 years.

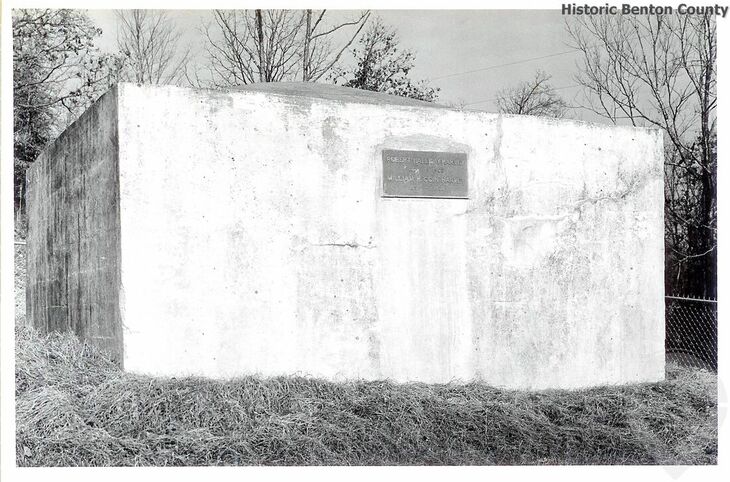

Harvey had failed at most of his grand plans, but he had known the love of a fine woman, a woman who knew that his greatness lay not in his plans but in himself. Mrs. Harvey saw her husband laid to rest in a chaste, simple mausoleum where his long-dead son lay. The tomb lies at the side of the shady lagoon where his gondolas once floated gaily by with singing oarsmen. The decaying village is out of site while the peace and beauty which first brought him to Monte Ne is all around him.

On the night of February 11, 1936, Coin Harvey, the most fabulous man who ever lived in Arkansas, died. Perhaps he died with a broken heart, no one knows but his wife who was with him. She was the former Mae Leake of Springfield, Mo., who for a quarter of a century had been his secretary and close friend. They were married in 1929, when Harvey finally got a divorce from his first wife after a separation of 30 years.

Harvey had failed at most of his grand plans, but he had known the love of a fine woman, a woman who knew that his greatness lay not in his plans but in himself. Mrs. Harvey saw her husband laid to rest in a chaste, simple mausoleum where his long-dead son lay. The tomb lies at the side of the shady lagoon where his gondolas once floated gaily by with singing oarsmen. The decaying village is out of site while the peace and beauty which first brought him to Monte Ne is all around him.

Harvey and his son are buried in a mausoleum at Monte Ne. This tomb had to be moved in the 1960s when Beaver Lake was built, otherwise it would have been under the lake.

People at Monte Ne refuse to believe that Coin Harvey died a cynic. They believe that he regained his faith in his times and got his bearings straight from the same source that the rest of us so often have. While he was still alive, the Joyzelle Camp for Girls was established just beyond his ill-fated pyramid. Harvey had said he "didn't like children," but when the girls held their water plays on the lagoon or gathered for their campfire ceremonies, the old gentleman was always seen coming down from his home on the hill to see the "goings on." Perhaps he did decide there was still fresh hope for our civilization. Perhaps there was no need for the pyramid after all.