During the Civil War, there were some minor conflicts in Bentonville, but no major battles within the city limits, even though the war did eventually inflict a heavy toll on the little town.

As the Union army was pushing through southern Missouri and into northwest Arkansas, they found little resistance, that was until they came to Dunagin’s farm around a half mile north of Avoca. The southern forces knew they had to at least try to stop the advance of the Union until they could get reinforcements, so they set up an ambush at Dunagin’s farm. The Confederate forces stationed themselves on each side of the road in the shrubs. When the Union troops came up the road, they were fired upon from both sides and were stopped from advancing at that time. The battle was said to have only taken a couple of minutes, but this set the stage for what was going to happen in Bentonville.

The first encounter in Bentonville occurred on February 18, 1862, when a Union cavalry and a light artillery unit were coming down the old wire (telegraph) road heading for Bentonville. About four miles east of town, probably around where highways 62 and 102 meet today, the Union forces surprised a dismounted Confederate cavalry unit. It doesn’t appear they took any prisoners at this time, but the Union forces did take some of the Confederates’ horses, along with all their bridles and saddles. The Union forces then roared into Bentonville about 12:20 p.m. on that day. The night before, the Confederates had made camp in Bentonville, and there were soldiers who were left behind cleaning up. The Union soldiers caught the Confederates off guard. There is some question as to whether there was a skirmish at this time or whether the Confederates just gave up. If there was much of a fight, it was brief. The Union forces captured 32 Confederate soldiers and four wagons of food and equipment, along with 36 horses, mail, Confederate quartermaster paperwork, a sum of Confederate currency, and an Arkansas 17th regiment flag which had been flying above the courthouse. Once the town was secured, the Union forces gathered the inhabitants of town who were administered the oath of allegiance to the Union. By 7:30 p.m., the Union soldiers had left town to return to the main Union force.

It was what happened next that totally changed the look of Bentonville. After the Union forces had left town, it appears that one soldier (from the Fifth Missouri Cavalry), either with or without permission, returned to town. He is said to have come back to town to fill up his canteen with whiskey. Either a Confederate soldier or a southern sympathizer shot the soldier in the head twice, then they hid the soldier’s body in an outhouse. The next day, a Union search party was sent out to try to find the missing soldier, and they found his body. The Union soldiers became upset with their friend's death, and began torching buildings in town to avenge the death of their comrade. As soon as the commander of the Union forces found out what was going on in Bentonville, he commanded his forces to stop the burning. By this time much of the town had been burned, with a total of thirty-six buildings destroyed.

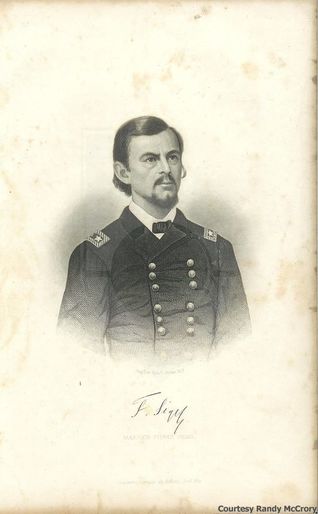

The next confrontation in Bentonville took place not long after, on March 6, 1862. Union forces marched through Bentonville on that day to their camp at Sugar Creek. The Union troops had left McKissick Springs to meet up with the main forces at Sugar Creek. They started moving through Bentonville about 8 am. General Franz Sigel was assigned to take the rear guard as Union forces were leaving town. The general had been warned not to play around like he had done at Wilson’s Creek where he had gotten some of his forces unnecessarily killed, and he himself had almost been captured. Sigel’s rear guard consisted of about six hundred men and six large guns. On that morning, he decided to sit down for breakfast at the Eagle Hotel (where the Massey Hotel/Phat Tire Bike Shop is now). The men had their rifles stacked and were resting until the general finished his breakfast. When the general was about ready to start eating his breakfast, he received word that Confederate forces were moving into town. He quickly cut himself a large slice of ham and out the door he went.

Sigel ran from the hotel, ordering his forces to retreat to the wooded area about 2 miles north of Bentonville. A group of soldiers who had been coming in from Osage Mills met him there, saying the Confederates were on their trail all the way there. The Confederate plan was to surround and capture Gen. Sigel’s forces. The Ist Missouri Cavalry attacked Sigel’s forces from the south to try to cut off their retreat. The Union company of the 36th Illinois were surprised and captured, just to be freed when Sigel’s withdrawing forces ran into them. General McIntosh sent about 3,000 Cavalry soldiers up a northerly road trying to get behind Sigel’s forces, but they went too far and had to backtrack three miles. Sigel turned east toward Sugar Creek, but found that Confederate soldiers had almost surrounded them. General Sigel was heard to have said, “Damn it, I’ll be caught here worse than I was at Wilson’s Creek, and all because I tried to have a good breakfast.” Just as the Confederates were about to capture Sigel’s forces, the Union troops at Sugar Creek heard the cannon fire, and the Confederates ran face to face into two Union divisions. At this time both sides set up artillery and kept firing until nightfall. This was one of the last events that happened before the battle of Pea Ridge.

Many years later, on March 9, 1887, General Sigel returned to Bentonville for one of the reunions. He sat down at the Eagle Hotel and requested to the waitress that he be allowed to finish his breakfast this time. The waitress replied to him, “Why, what do you mean sir?” He responded, “I was run out of Bentonville in March of 1862, and was eating at this very table.” The general was allowed to enjoy a long breakfast uninterrupted. He stayed in the same room where he had earlier stayed at the hotel, and he ate the same breakfast as 25 years earlier.saying the hotel was just how he remembered it. At that time he said he was writing his memoirs of the Civil War and visited the Pea Ridge battlefield several times during his stay. He also visited with several people who fought in the Confederate army.

Bentonville continued to suffer during the war. As armies from both sides passed through Bentonville would find a vacated house, they would burn the house down, assuming that the house belonged to a sympathizer for the other side. Both armies accused the other side of the burning of the courthouse in the middle of the square. It is said, according to the best authority, that two churches, the Masonic hall, and a school building were all burned to keep the Union army from using them. There were also bushwhackers and bandits who rode through to torture and rob, and they also set fire to houses. One local Presbyterian pastor who tried taking some grain to the mill to be ground was found dead.

By the end of the war, food was as scarce as was the money with which to buy it. A barrel of flour would cost $300, shoes $150, and coffee $50 a pound. The soldiers took what they wanted from the locals. Farm fences that were in the area of a Civil War camp usually disappeared quickly to be used for firewood by the armies. However, farmers who proved their claims and had pledged allegiance to the federal government during the war were reimbursed for their losses after the war was over. There are still records of this on file at the Benton County archives. By the time the war was finished, it was said there were only 12 structures left standing in Bentonville. The buildings that were left were the Eagle Hotel, two stores, the jail, and eight residences. By the end of the war, the remaining citizens were facing many hardships, but the people of Bentonville were determined to rebuild and return to a normal way of life.

One last tidbit about the Civil War is the history of “Shoemakers” cave. It was located about two miles west of Bentonville. During the Civil War, if the Union army caught people making shoes for the rebel army, they might just lose their lives. Because of the lack of shoes for Confederate soldiers, the local shoemakers looked for a place where they could make shoes without being caught. They selected that cave because it was out of the way, and the opening couldn’t easily be seen or found. There they worked in safety without the fear of easily being caught, putting out shoes for the Confederate soldiers.

As the Union army was pushing through southern Missouri and into northwest Arkansas, they found little resistance, that was until they came to Dunagin’s farm around a half mile north of Avoca. The southern forces knew they had to at least try to stop the advance of the Union until they could get reinforcements, so they set up an ambush at Dunagin’s farm. The Confederate forces stationed themselves on each side of the road in the shrubs. When the Union troops came up the road, they were fired upon from both sides and were stopped from advancing at that time. The battle was said to have only taken a couple of minutes, but this set the stage for what was going to happen in Bentonville.

The first encounter in Bentonville occurred on February 18, 1862, when a Union cavalry and a light artillery unit were coming down the old wire (telegraph) road heading for Bentonville. About four miles east of town, probably around where highways 62 and 102 meet today, the Union forces surprised a dismounted Confederate cavalry unit. It doesn’t appear they took any prisoners at this time, but the Union forces did take some of the Confederates’ horses, along with all their bridles and saddles. The Union forces then roared into Bentonville about 12:20 p.m. on that day. The night before, the Confederates had made camp in Bentonville, and there were soldiers who were left behind cleaning up. The Union soldiers caught the Confederates off guard. There is some question as to whether there was a skirmish at this time or whether the Confederates just gave up. If there was much of a fight, it was brief. The Union forces captured 32 Confederate soldiers and four wagons of food and equipment, along with 36 horses, mail, Confederate quartermaster paperwork, a sum of Confederate currency, and an Arkansas 17th regiment flag which had been flying above the courthouse. Once the town was secured, the Union forces gathered the inhabitants of town who were administered the oath of allegiance to the Union. By 7:30 p.m., the Union soldiers had left town to return to the main Union force.

It was what happened next that totally changed the look of Bentonville. After the Union forces had left town, it appears that one soldier (from the Fifth Missouri Cavalry), either with or without permission, returned to town. He is said to have come back to town to fill up his canteen with whiskey. Either a Confederate soldier or a southern sympathizer shot the soldier in the head twice, then they hid the soldier’s body in an outhouse. The next day, a Union search party was sent out to try to find the missing soldier, and they found his body. The Union soldiers became upset with their friend's death, and began torching buildings in town to avenge the death of their comrade. As soon as the commander of the Union forces found out what was going on in Bentonville, he commanded his forces to stop the burning. By this time much of the town had been burned, with a total of thirty-six buildings destroyed.

The next confrontation in Bentonville took place not long after, on March 6, 1862. Union forces marched through Bentonville on that day to their camp at Sugar Creek. The Union troops had left McKissick Springs to meet up with the main forces at Sugar Creek. They started moving through Bentonville about 8 am. General Franz Sigel was assigned to take the rear guard as Union forces were leaving town. The general had been warned not to play around like he had done at Wilson’s Creek where he had gotten some of his forces unnecessarily killed, and he himself had almost been captured. Sigel’s rear guard consisted of about six hundred men and six large guns. On that morning, he decided to sit down for breakfast at the Eagle Hotel (where the Massey Hotel/Phat Tire Bike Shop is now). The men had their rifles stacked and were resting until the general finished his breakfast. When the general was about ready to start eating his breakfast, he received word that Confederate forces were moving into town. He quickly cut himself a large slice of ham and out the door he went.

Sigel ran from the hotel, ordering his forces to retreat to the wooded area about 2 miles north of Bentonville. A group of soldiers who had been coming in from Osage Mills met him there, saying the Confederates were on their trail all the way there. The Confederate plan was to surround and capture Gen. Sigel’s forces. The Ist Missouri Cavalry attacked Sigel’s forces from the south to try to cut off their retreat. The Union company of the 36th Illinois were surprised and captured, just to be freed when Sigel’s withdrawing forces ran into them. General McIntosh sent about 3,000 Cavalry soldiers up a northerly road trying to get behind Sigel’s forces, but they went too far and had to backtrack three miles. Sigel turned east toward Sugar Creek, but found that Confederate soldiers had almost surrounded them. General Sigel was heard to have said, “Damn it, I’ll be caught here worse than I was at Wilson’s Creek, and all because I tried to have a good breakfast.” Just as the Confederates were about to capture Sigel’s forces, the Union troops at Sugar Creek heard the cannon fire, and the Confederates ran face to face into two Union divisions. At this time both sides set up artillery and kept firing until nightfall. This was one of the last events that happened before the battle of Pea Ridge.

Many years later, on March 9, 1887, General Sigel returned to Bentonville for one of the reunions. He sat down at the Eagle Hotel and requested to the waitress that he be allowed to finish his breakfast this time. The waitress replied to him, “Why, what do you mean sir?” He responded, “I was run out of Bentonville in March of 1862, and was eating at this very table.” The general was allowed to enjoy a long breakfast uninterrupted. He stayed in the same room where he had earlier stayed at the hotel, and he ate the same breakfast as 25 years earlier.saying the hotel was just how he remembered it. At that time he said he was writing his memoirs of the Civil War and visited the Pea Ridge battlefield several times during his stay. He also visited with several people who fought in the Confederate army.

Bentonville continued to suffer during the war. As armies from both sides passed through Bentonville would find a vacated house, they would burn the house down, assuming that the house belonged to a sympathizer for the other side. Both armies accused the other side of the burning of the courthouse in the middle of the square. It is said, according to the best authority, that two churches, the Masonic hall, and a school building were all burned to keep the Union army from using them. There were also bushwhackers and bandits who rode through to torture and rob, and they also set fire to houses. One local Presbyterian pastor who tried taking some grain to the mill to be ground was found dead.

By the end of the war, food was as scarce as was the money with which to buy it. A barrel of flour would cost $300, shoes $150, and coffee $50 a pound. The soldiers took what they wanted from the locals. Farm fences that were in the area of a Civil War camp usually disappeared quickly to be used for firewood by the armies. However, farmers who proved their claims and had pledged allegiance to the federal government during the war were reimbursed for their losses after the war was over. There are still records of this on file at the Benton County archives. By the time the war was finished, it was said there were only 12 structures left standing in Bentonville. The buildings that were left were the Eagle Hotel, two stores, the jail, and eight residences. By the end of the war, the remaining citizens were facing many hardships, but the people of Bentonville were determined to rebuild and return to a normal way of life.

One last tidbit about the Civil War is the history of “Shoemakers” cave. It was located about two miles west of Bentonville. During the Civil War, if the Union army caught people making shoes for the rebel army, they might just lose their lives. Because of the lack of shoes for Confederate soldiers, the local shoemakers looked for a place where they could make shoes without being caught. They selected that cave because it was out of the way, and the opening couldn’t easily be seen or found. There they worked in safety without the fear of easily being caught, putting out shoes for the Confederate soldiers.

Note: The color images on this page are from a local 2017 reenactment of the battle of Pea Ridge.