The Bentonville Railroad and Frisco's Bentonville Branch

By Tom Duggan

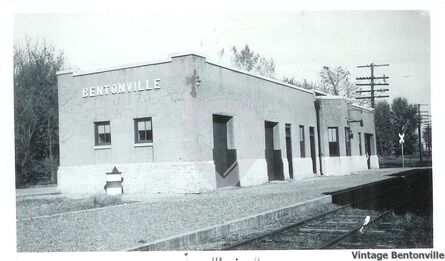

The look of the train depot has changed from when it was first built. It was originally a small two story depot. The second story was removed when the Frisco Railroad bought the line. They also added onto the front and the back of the older depot.

Under Frisco ownership the Bentonville Branch first had nine depots excluding the mainline depot at Rogers. The stations at Bentonville, Gravette, Southwest City, and Grove enjoyed daytime agents-telegraphers. Grove was also the site for the end of line turntable operated by manpower alone. A water tank was added at Bentonville in 1906. Coaling stations in the form of low sided coal cars were added at Bentonville and Grove between 1907 and 1913. Grove later had a 60-foot steel turntable. The Bentonville coaling station was gone by 1917 while the Grove coaling facility lasted until 1927. From the late 1920s the Frisco's Central Division locomotives, including those used on the Bentonville Branch, burned oil. For at least the first 14 years of Frisco ownership the principal locomotive was No. 31, a tiny Hinkley locomotive that dated to 1876. In 1914, the Frisco Man Magazine carried a picture of No. 31 noting it was the oldest on the entire Frisco system.

A motor car arrived on the Bentonville Branch in 1911, the same year passenger fares increased to three cents per mile from two. The 70 foot long steel car was divided into five compartments with a 23 foot long passenger compartment seating 48, two ten foot compartments for smokers and "colored passengers", and an eight-foot baggage compartment. The 200 horsepower gasoline engine drove generators that powered two electric traction motors. The car, which cost about $25,000, must have been unsuited for the Bentonville Branch as steam engines soon resumed handling passenger runs.

The highest frequency of passenger service was between 1913 and 1917. The Frisco operated a daily passenger roundtrip named the Western and Eastern Express respectively. The express runs operated at average speeds of 16.8 mph (1913) to 19.2 mph (1925) for the one-way trip. A combination Railway Post Office-baggage-passenger car initiated service on August 7, 1901. Residents along the Bentonville Branch could read the St. Louis evening papers no later than noon the following day thanks to the St. Louis overnight train that served Rogers. The passenger run departed Rogers between 8:00 AM and 9:00 AM and returned in late afternoon. A slower mixed train carrying freight and passengers operated over the same route daily. Bentonville and Rogers also had two daily runs thus giving Bentonville four daily trains to and from Rogers. After World War I, the combination of automobiles, trucks, and paved roads began to erode passenger and freight rail service.

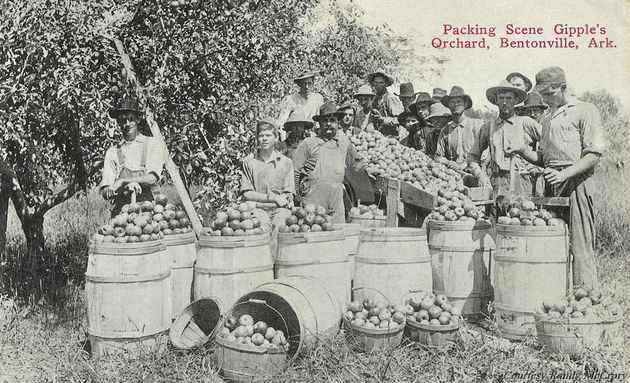

The Bentonville Branch relied on agriculture for freight revenues. The Benton County peach harvest, which began in 1891, peaked in 1913 and declined rapidly. Benton County's apple harvest reached commercial levels in 1896 and expanded rapidly. It peaked in 1919 with five million bushels worth $5 million. The apple and peach business in Northwest Arkansas was highly sensitive to weather. In 1896 a late freeze wiped out both apple and peach crops. In 1903 a late freeze again wiped out apple and peach production. A late freeze in 1908 had the same severe effect on apple and peach growers.

A motor car arrived on the Bentonville Branch in 1911, the same year passenger fares increased to three cents per mile from two. The 70 foot long steel car was divided into five compartments with a 23 foot long passenger compartment seating 48, two ten foot compartments for smokers and "colored passengers", and an eight-foot baggage compartment. The 200 horsepower gasoline engine drove generators that powered two electric traction motors. The car, which cost about $25,000, must have been unsuited for the Bentonville Branch as steam engines soon resumed handling passenger runs.

The highest frequency of passenger service was between 1913 and 1917. The Frisco operated a daily passenger roundtrip named the Western and Eastern Express respectively. The express runs operated at average speeds of 16.8 mph (1913) to 19.2 mph (1925) for the one-way trip. A combination Railway Post Office-baggage-passenger car initiated service on August 7, 1901. Residents along the Bentonville Branch could read the St. Louis evening papers no later than noon the following day thanks to the St. Louis overnight train that served Rogers. The passenger run departed Rogers between 8:00 AM and 9:00 AM and returned in late afternoon. A slower mixed train carrying freight and passengers operated over the same route daily. Bentonville and Rogers also had two daily runs thus giving Bentonville four daily trains to and from Rogers. After World War I, the combination of automobiles, trucks, and paved roads began to erode passenger and freight rail service.

The Bentonville Branch relied on agriculture for freight revenues. The Benton County peach harvest, which began in 1891, peaked in 1913 and declined rapidly. Benton County's apple harvest reached commercial levels in 1896 and expanded rapidly. It peaked in 1919 with five million bushels worth $5 million. The apple and peach business in Northwest Arkansas was highly sensitive to weather. In 1896 a late freeze wiped out both apple and peach crops. In 1903 a late freeze again wiped out apple and peach production. A late freeze in 1908 had the same severe effect on apple and peach growers.

Apples shipped from Benton County included three types. Perishable green apples of the highest value were shipped in express cars attached to passenger trains. Lower value evaporated apples were processed in one of many wood-fired evaporators in Benton County. The dried apples were shipped out by rail in wooden barrels. The least valuable apples were used for vinegar. In 1919 Benton County shipped out 4,055 cars of apples. Most of the Benton County apple shipments originated in the towns of Rogers, Bentonville, Centerton and Hiwassee, the last three being on the Bentonville Branch. From 1919 onwards, there was a sharp decline in the apple harvest caused by late frosts, low prices, and infestations of fruit tree rust. In 1915, Arkansas voted for statewide prohibition. Distillers such as Bentonville's Macon-Carson went out of business. By the mid 1920's the bugs and tree rust problems were so severe that up to nine applications of costly agricultural chemicals were required for each apple crop.

Northwest Arkansas apple growers were very conservative. They continued to produce quantities of Arkansas Black apples even as the market shifted to new varieties. Even as late as 1928, Bentonville shipped 153 cars of apples followed by Hiwasse with 117 and Centerton with 74 carloads. The Bentonville Branch also had some strawberry production. In 1912, the Frisco offered to operate a special "berry train" on the Branch. It is unknown if a special berry train operated on the Branch.

In addition to Benton County fruits, the branch also carried wheat grown in the Grove area. In 1925 a newspaper reported small shipments of cotton from Grove. Many of the stations along the line had livestock pens for seasonal shipments of cattle. The line initially had a good volume of forest products, especially railroad ties, but by the 1920s this traffic source had withered away. Although the Bentonville Branch crossed the Kansas City Southern Railway main line at Gravette, AR, the two railroads exchanged virtually no freight traffic. In 1930, Gravette, population 812, had the dubious distinction of having two railroad stations.

The Western and Eastern Express passenger service was abolished in 1927 and replaced by a daily mixed train. In 1933, a Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday mixed train replaced the daily mixed train. The thrice-weekly mixed train also ended the line's Railway Post Office service on May 1, 1933. The mixed train operated at the leisurely speed of some 15 miles per hour. In 1933, the Frisco experimented with a penny a mile promotion on its Arkansas routes. It soon withdrew the special promotion as very few people could afford to ride the train. In later years stations at Bentonville, Centerton, Hiwasse, and Dodge, Oklahoma became flag stops.

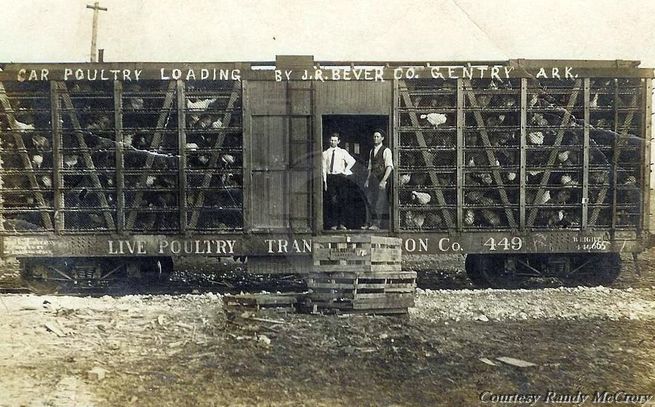

Bentonville Branch freight traffic, the lifeblood of railroading, continued to show a steady decline. Between 1923 to 1929, the line handled an annual average of 1,417 cars of freight. Between 1930 and 1934, the average annual freight volume collapsed to 757 cars. From 1934 to 1938, the line averaged only 519 cars. The Dodge, OK depot handled no freight between 1930 and 1940 while Hiawassee saw no freight between 1937 and 1940. In 1939, Benton County's developing poultry industry generated 2,000 carloads of poultry. Unfortunately, for the Bentonville Branch the poultry producers used trucks, as they were faster and less expensive than rail. Coupled with the decline in business was the poor physical condition of the line. Most of the 56 to 60-pound track, dating to 1900-01, was laid without ballast. The ties, untreated white oak or softwood, were in an advanced state of deterioration. The 26 timber trestle bridges were also in poor condition.

Northwest Arkansas apple growers were very conservative. They continued to produce quantities of Arkansas Black apples even as the market shifted to new varieties. Even as late as 1928, Bentonville shipped 153 cars of apples followed by Hiwasse with 117 and Centerton with 74 carloads. The Bentonville Branch also had some strawberry production. In 1912, the Frisco offered to operate a special "berry train" on the Branch. It is unknown if a special berry train operated on the Branch.

In addition to Benton County fruits, the branch also carried wheat grown in the Grove area. In 1925 a newspaper reported small shipments of cotton from Grove. Many of the stations along the line had livestock pens for seasonal shipments of cattle. The line initially had a good volume of forest products, especially railroad ties, but by the 1920s this traffic source had withered away. Although the Bentonville Branch crossed the Kansas City Southern Railway main line at Gravette, AR, the two railroads exchanged virtually no freight traffic. In 1930, Gravette, population 812, had the dubious distinction of having two railroad stations.

The Western and Eastern Express passenger service was abolished in 1927 and replaced by a daily mixed train. In 1933, a Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday mixed train replaced the daily mixed train. The thrice-weekly mixed train also ended the line's Railway Post Office service on May 1, 1933. The mixed train operated at the leisurely speed of some 15 miles per hour. In 1933, the Frisco experimented with a penny a mile promotion on its Arkansas routes. It soon withdrew the special promotion as very few people could afford to ride the train. In later years stations at Bentonville, Centerton, Hiwasse, and Dodge, Oklahoma became flag stops.

Bentonville Branch freight traffic, the lifeblood of railroading, continued to show a steady decline. Between 1923 to 1929, the line handled an annual average of 1,417 cars of freight. Between 1930 and 1934, the average annual freight volume collapsed to 757 cars. From 1934 to 1938, the line averaged only 519 cars. The Dodge, OK depot handled no freight between 1930 and 1940 while Hiawassee saw no freight between 1937 and 1940. In 1939, Benton County's developing poultry industry generated 2,000 carloads of poultry. Unfortunately, for the Bentonville Branch the poultry producers used trucks, as they were faster and less expensive than rail. Coupled with the decline in business was the poor physical condition of the line. Most of the 56 to 60-pound track, dating to 1900-01, was laid without ballast. The ties, untreated white oak or softwood, were in an advanced state of deterioration. The 26 timber trestle bridges were also in poor condition.

This is an example of one of the poultry rail cars you would see in the 1930's and 1940's

In 1938, the Bentonville Branch was rented by Twentieth-Century Fox for several railroad scenes in the film Jesse James using an engine from the Dardanelle & Russellville Railroad and cars from the Frisco. Older local residents still recall with clarity the railroad scenes shot near Hiwasse and Southwest City, Missouri. The film's nighttime train robbery took place in a winding ravine on immaculately ballasted track. The robbery was filmed on the Kansas City Southern Railway's immaculately ballasted the line at Neosho, Missouri as the Bentonville Branch had no ballast.

The Bentonville Branch also was the workplace for two interesting individuals. The first individual was Joseph H. Rackerby of Rogers. He served as the second Rogers postmaster from October 1881 to July 1882. Rackerby, who was born in 1833, then worked as a railway mail clerk. In July 1901, he began work as the railway mail clerk on the Bentonville passenger train at the age of 68 years. He was said to be the oldest railway mail clerk west of the Mississippi. Rackerby toiled on the Bentonville Branch for nearly four more years until poor health caused his resignation in early 1905. He died in October 1907 in Rogers.

The second interesting individual was Columbus Burt Coleman of Bentonville who was profile in the January 1929 issue of the Frisco Magazine. Born in 1860, Coleman celebrated 50 years of Frisco service in 1929. His period of service covered a time of great change in the railroad industry. About 1901 Coleman became engineer on the Bentonville Branch passenger train. He worked as passenger engineer for 25 years. Coleman must have seen the rise and decline of the Branch. He had a farm in Bentonville where he raised apples and other fruits. Burt Coleman then transferred to the Frisco's St. Paul Branch where he worked on a six days a week mixed train.

On December 22, 1939 the Frisco, under the control of receivers since 1935, applied to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for permission to abandon the Bentonville Branch for 41.01 miles from a point west of Bentonville to Grove, OK. Between 1934 and October 1939, the Bentonville Branch had lost a total of $171,880 with no visible prospects for future profitable operation. Hearings were held at affected communities. The Grand River reclamation project at Grove, OK was cited as a reason to maintain the line. The ICC noted that the new project was uncertain in its timing and it might take years for the Bentonville Branch to benefit from industrial activity, if any, in the Grove area. Several parties wanted the line to operate as a means of keeping trucking rates low. The ICC rejected this argument by reiterating its policy that no railroad was obliged to operate a loss-making branch as a means of keeping trucking rates low.

The ICC held a hearing in Washington, DC on July 10, 1940 to consider the abandonment application. It ruled on July 31, 1940 that the 41.01 miles of track west of Bentonville be abandoned, as there was no need for the line. The final order for abandonment became effective 40 days after July 31, 1940. The 40-day period would enable shippers to move equipment off the line and permit the Frisco to advise interested parties of the abandonment. Service west of Bentonville ended on September 9, 1940. Post 1940 rail service continued to Bentonville by extra trains that ran as needed.

The Bentonville Branch also was the workplace for two interesting individuals. The first individual was Joseph H. Rackerby of Rogers. He served as the second Rogers postmaster from October 1881 to July 1882. Rackerby, who was born in 1833, then worked as a railway mail clerk. In July 1901, he began work as the railway mail clerk on the Bentonville passenger train at the age of 68 years. He was said to be the oldest railway mail clerk west of the Mississippi. Rackerby toiled on the Bentonville Branch for nearly four more years until poor health caused his resignation in early 1905. He died in October 1907 in Rogers.

The second interesting individual was Columbus Burt Coleman of Bentonville who was profile in the January 1929 issue of the Frisco Magazine. Born in 1860, Coleman celebrated 50 years of Frisco service in 1929. His period of service covered a time of great change in the railroad industry. About 1901 Coleman became engineer on the Bentonville Branch passenger train. He worked as passenger engineer for 25 years. Coleman must have seen the rise and decline of the Branch. He had a farm in Bentonville where he raised apples and other fruits. Burt Coleman then transferred to the Frisco's St. Paul Branch where he worked on a six days a week mixed train.

On December 22, 1939 the Frisco, under the control of receivers since 1935, applied to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for permission to abandon the Bentonville Branch for 41.01 miles from a point west of Bentonville to Grove, OK. Between 1934 and October 1939, the Bentonville Branch had lost a total of $171,880 with no visible prospects for future profitable operation. Hearings were held at affected communities. The Grand River reclamation project at Grove, OK was cited as a reason to maintain the line. The ICC noted that the new project was uncertain in its timing and it might take years for the Bentonville Branch to benefit from industrial activity, if any, in the Grove area. Several parties wanted the line to operate as a means of keeping trucking rates low. The ICC rejected this argument by reiterating its policy that no railroad was obliged to operate a loss-making branch as a means of keeping trucking rates low.

The ICC held a hearing in Washington, DC on July 10, 1940 to consider the abandonment application. It ruled on July 31, 1940 that the 41.01 miles of track west of Bentonville be abandoned, as there was no need for the line. The final order for abandonment became effective 40 days after July 31, 1940. The 40-day period would enable shippers to move equipment off the line and permit the Frisco to advise interested parties of the abandonment. Service west of Bentonville ended on September 9, 1940. Post 1940 rail service continued to Bentonville by extra trains that ran as needed.

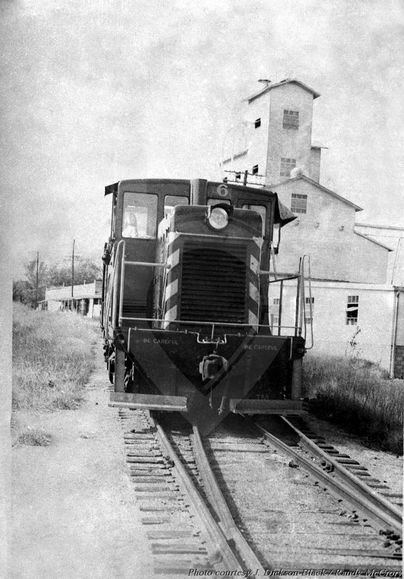

The Frisco became part of Burlington Northern Inc. in November 1980. The Burlington Northern, in common with other large railroad systems, began to sell lines that did not meet criteria for profitability or strategic fit. The Frisco's former Central Division-Fort Smith Subdivision from South Monett, Missouri to South Fort Smith, Arkansas (including the Bentonville Branch) became the Arkansas And Missouri Railroad Company in August 1986. In 1990, the Bentonville branch was cut back by the new owner. [Note: The branch served two industrial customers located in east Bentonville, but the branch has recently stopped all operation in Bentonville. The line now ends at the Rogers and Bentonville city limits.]

The Bentonville Railroad was conceived of civic pride. Although it failed to link up with a non-Frisco railroad, it led to the creation of the Bentonville Branch. The Branch in turn served a vital function for perhaps thirty years in the lives of the residents living along the line. The Frisco depot in Bentonville has been carefully restored and served for some years as the headquarters for the Bentonville -Bella Vista Chamber of Commerce. [More recently the building has been the offices of Celebrate Magazine.] West of Bentonville the careful observer can pick out signs of the right of way. If you listen hard enough perhaps you can hear the excited chatter of passengers as they listen for the whistle of the train that was their companion in a time past.

The Bentonville Railroad was conceived of civic pride. Although it failed to link up with a non-Frisco railroad, it led to the creation of the Bentonville Branch. The Branch in turn served a vital function for perhaps thirty years in the lives of the residents living along the line. The Frisco depot in Bentonville has been carefully restored and served for some years as the headquarters for the Bentonville -Bella Vista Chamber of Commerce. [More recently the building has been the offices of Celebrate Magazine.] West of Bentonville the careful observer can pick out signs of the right of way. If you listen hard enough perhaps you can hear the excited chatter of passengers as they listen for the whistle of the train that was their companion in a time past.