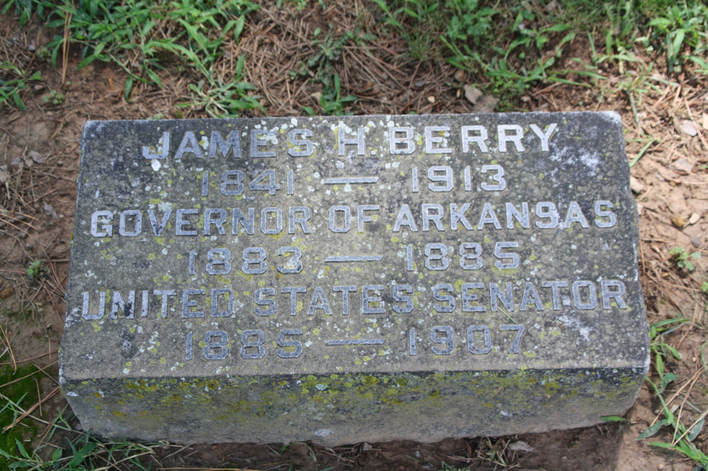

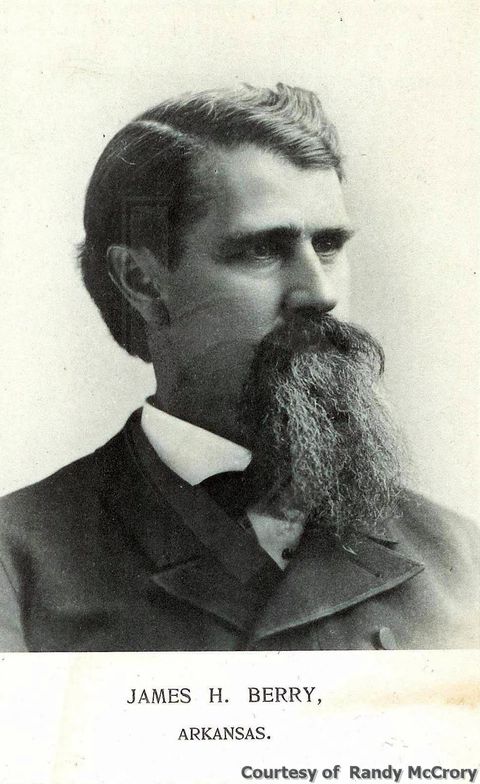

An Autobiography of James H. Berry, written at the request of his family a few months before his death (published 1913)

I was born on a farm in Jackson County, Alabama, on May 15th 1841. My father was James M. Berry and my mother was Isabelle Jane Orr. In 1848, when I was seven and a half years old, I moved to Carrollton, Carroll County, Arkansas.

There were ten children of us who lived to be grown: Granville, the oldest; Mary, who married Col. Sam W. Peel; Fannie, who married Rufus Polk; Dick; and then I came next; then Arkansas, called “Canty,” who married Captain Arch McKennon; Willie who was killed during the war; Sophronia, who married Andrew Forrest; Albert; Emma, the youngest, who married Dr. A. M. McKennon. They are all dead except Sophronis Forrest and myself.

I was raised on a small farm adjoining the village of Carrolton. My father for a part of the time sold goods in the town and I attended the village school some time during the winter and learned to read and write a little, and something of arithmetic. When I was 17 years old my father sent me to the Berryville Academy 18 miles from our home, which was the best school in that locality, and I attended that school for 10 months.

In 1860 my mother died after a long illness, and the expenses attending her sickness forced my father to sell our home, and I was taken from the school and sent to Yellville, Arkansas, to clerk in the store of James H. Berry, who was a cousin of my father. I remained there until the war began, when I came back to our old home in Carrollton and joined the Confederate Army on the 19th of September, 1861. On the same day that I enlisted I was elected Second Lieutenant in what was afterwards Company E, Sixteenth Arkansas Infantry.

We went into winter quarters that winter at Elm Springs Arkansas, and remained there until February 1862, when we were sent to meet General Price, who was retreating from Missouri. He continued to retreat to the Boston Mountains in Arkansas, and early in March, 1862, General VanDorn took command and we went from there to Pea Ridge, Arkansas, where on the 7th and 8th of March we fought the battle called by the Union soldiers “Pea Ridge” and called "Elk Horn” by the Confederates. We were defeated, and retreated from Pea Ridge to the Arkansas River, and from there we went by way of Memphis to Corinth, Mississippi, where we joined General Beauregard’s army on about April 15th, 1862. A few days afterwards my regiment, being on outpost duty, became engaged and we lost 17 killed and wounded. The last of May General Beauregard evacuated Corinth and moved to Tupelo, Mississippi, and we remained at Tupelo and Satillo until September, when we went to Iuka, Mississippi.

On the 19th of September, 1862, one year from the day when I enlisted we fought the fight at Iuka. We went from Iuka and joined a portion of the army of VanDorn at Holly Springs, Mississippi, and on the 3rd and 4th of October, 1862, we fought the battle of Corinth, Mississippi. General VanDorn commanded the Confederate forces and General Rosencrans the Union Forces. We attacked their breastworks in a terrible engagement and the brigade to which I belonged, consisting of about 1500 or 1600 men, lost 402 men in less the 30 minutes. I was badly wounded, resulting in the loss of my right leg. I fell into the hands of the Federal Army and was sent to a hospital at Iuka, Mississippi. I remained in the hospital there for two months and was then taken to Rienzi, Mississippi, by a relative of mine – my father’s aunt. I remained there for several months and it was five months from the time I was wounded until I joined my regiment at Port Hudson, Louisiana.

While I was at a private house some 18 miles from Port Hudson, where I went to await for my brother-in-law, Lieut. McKennon, to try to get a furlough to take me home, Port Hudson became besieged by General Banks, leaving me on the outside. I remained there during the entire siege of 49 days. My younger brother, Willie, was at Port Hudson at the time, although he had been discharged from the army a few days before because he had served out the twelve months for which he had enlisted and, not being 18 years old, was not subject to military duty under the conscript law. When Banks surrounded the place he was on the inside of Port Hudson and, although not required to do so, he took his gun and went back into the Company.

When Port Hudson surrendered, all the privates, my brother amongst them, were paroled. Lieut McKennon, with the other officers, was taken to Johnson Island, Ohio. Two of the officers of my regiment, Capt. Poynor of my own Company and Lieut. Bailey of Company D, made their escape from Port Hudson after the surrender, and they came to the house where I was staying. My brother came with them and all of us together made our way back to Arkansas, crossing the Mississippi River in skiffs and traveling in various ways. Part of the time I rode a mule while they walked and we finally reached Little Rock, Arkansas. Capt. Poyner and Lieut. Bailey went from Little Rock across the mountain on foot to our old home in Carroll County, and my brother and I took a stage and came to Ozark, Arkansas, where my sister and father lived. We reached there in August, 1863, and stayed there for some two months, and from there I went back to our old home in Carroll County, staying with my sister, Mrs. Sam W. Peel, who was still living there. The country was in a very disturbed condition. There were quite a number of Confederate soldiers, some of them refugees from Missouri and some who had been paroled from the army at Port Hudson and at Vicksburg. Many of them were what were called “Independent Companies,” but no regular organized army was in the immediate section. The Federal soldiers came in from time to time and more or less fighting and skirmishing and killing was going on in the county.

I remained there as long as I dared, and then, with my sister, the wife of Lieut McKennon, crossed the mountain and went back to Ozark. While I was at Ozark the Fourteenth Kansas Cavalry, U.S.A., under Col. Brown, occupied the place. He required all the old men left at home to take the oath of allegiance to the Government, and sent for me and asked me to take the oath. I told him that I did not desire to take the oath of allegiance; that I was a Lieutenant in the Confederate Army; that I was a prisoner and that he had the right to send me to prison if he desired to do so, but that he had no right to require me to take the oath. He said that he did not wish to send a man to prison who had but one leg and was on crutches, but that he was under no obligations to protect me from the soldiers unless I did take the oath. I told him that I did not think the soldiers would hurt me and that I was willing to take it. He told me very curtly that I could retire. A few days after this he moved his regiment to Clarksville, Arkansas, 25 miles away, expecting to return, and the day the Federals left, Capt. McDonald of the Confederate Army, with some other Confederates, came into town.

McDonald told me that he and some 30 or 40 others were going south the next morning and that if I could get across the river that night and join them at daylight that he had an extra pony which I could ride and could go south with them. I managed to get an old man at 1 o’clock that night to set me across the river in a skiff and joined the soldiers on the other side and went with them to Monticello, Arkansas, where my old regiment was camped, reaching there in the fall of 1864. I remained at Monticello until February, 1865, and went from there to Shreveport, Louisiana, and then obtained a furlough from General Kirby Smith in person for 90 days.

I went from there to Texas and stayed with relatives in Tarrant and Ellis Counties until the first of May, when the Confederate Army west of the Mississippi disbanded. I was with General Cabell’s command at Corsicana when the soldiers broke up and went to their homes. I gave my watch, which my father had given me before the war for a horse and rode back to Ozark, reaching there about the 10th of June, 1865. I stayed with my sister and soon after began teaching a school, for three months, of some 30 children.

I had gotten acquainted, while in Ozark during the war, with Lizzie Quaile, whose father and mother lived there. Her father was still in Texas when I reached Ozark and did not get back until about September 1st. In the meantime I had seen her almost every day and we had promised each other that sometime in the future we would be married. When her father came home and learned of the situation, he informed her that he seriously objected to her marrying me, and that he proposed to send her off to Kentucky to school. She told me about it and I went and talked to him. He told me that he could not consent to the marriage; that I had no way to make a living; that he knew nothing against me, but that he was unwilling for his daughter to marry me because I had no means of support and no prospects. I told him that I was willing to wait a reasonable length of time, but that I would like for him to say that, if I could get along and make a living he would consent. He said there was no use in holding out hope in which in all probability could not be realized, and that we would have to give it up, and that he was going to send her to Kentucky to school. He then said he would like to know the course I proposed to pursue in regard to it. I told him that I had never asked her to marry me against his wishes, and that I did not know whether or not she would do so, but that she had told me that she did not wish to go to Kentucky to school, and that, rather than have her sent away against wishes, I would marry her if I could. He then said the only unkind words to me that he ever did say, and that was that I had better be careful. This was on Monday, and on Tuesday night at my aunt’s house we were married. We stayed with my sister for a few weeks and then went to Carrollton. I will say here that it was seventeen years from the time we married before Mr. Quaile and I spoke to each other. In 1882, the day after I was nominated for governor, I came from Little Rock to Ozark with Henry Carter, who had married my wife’s sister, and Gen. H. B. Armistead, a prominent man from Franklin county, and they urged me very earnestly that when we stopped off at Ozark that I should go to Mr. Quaile and offer him my hand. I told them that I was afraid he would not accept it, and they both said they were assured that he would do so. I thought the matter over and concluded that the time had come when I could go to him and that he could not very well come to me without having his motives misconstrued. In company with Henry Carter, I walked over to his house, and when he came out on the front porch I spoke to him and offered him my hand. He took my hand and asked me to walk into the house, and when he came out on the front porch I spoke to him and offered him my hand. He took my hand and asked me to walk into the house. I went in and we began to talk about the convention and the cotton crop, and never from that time until his death was the marriage mentioned between us. I want to say here that Mr. Quaile was a man of the very highest character, a splendid man in every way and respected wherever he was known. He was devoted to his family, and I never blamed him for objecting to the marriage. It was the most natural thing in the world that he should object, as I had absolutely nothing, not even a law license, and was on crutches. When I had daughters of my own I realized that, under the same conditions I would have done as he did.

After going back to Carrollton we lived for a time in a small house, about eight feet square, which had been built before the war for a milk house over the well. We ate with Col. Peel's family in a log house that he had built after the war, his house having been burned.

While I was teaching school at Ozark I had borrowed a law book wherever I could find one and was reading law, and I continued to read after I went back to Carrollton. On the first Monday in August, 1866, I was elected to the Legislature from Carroll county, being the youngest man in the Legislature. I was opposed in the race by four or five older men, but as two were to be elected, I was chosen as one of them. On my way to Little Rock I stopped over for a day in Ozark and secured my license to practice law. The session of the Legislature was a long one and the pay was six dollars a day, and that, together with the mileage, enabled me to save about three hundred dollars during the session. I went back to Carrollton after the adjournment and built a one-room log cabin, and we lived in that for two years. I went to work at such practice as I could get before the justice of the peace and the county court and occasionally in the circuit court. I also assisted the clerk of the court in his office at different times and made some money in that way.

In December, 1869, I sold my property at Carrollton and that, together with the money I had saved, enabled me to build a house at Bentonville, Ark., where we moved and where I have since lived. For a time after moving to Bentonville I practiced law in partnership with Col. S. W. Peel. In September, 1872, I was elected to the Legislature from Benton county. During the term for which I was elected, in May, 1874, what was known as the Brooks-Baxter war took place over the governorship of Arkansas and Governor Baxter called an extraordinary session of the Legislature, of which I was a member. The original Legislature was composed of a majority of Republicans, but numerous vacancies had occurred by reason of appointments to office, and these had been filled by Democrats. When the Legislature met, Mr. Tankersley speaker of the House, who was a Republican, had joined the Brooks side of the war then going on and did not appear in answer to the call of Governor Baxter. The majority of those being Democrats, we proceeded to remove Mr. Tankersley from the speakership and I was elected Speaker in his place. This extraordinary session of the Legislature while I was speaker called the constitutional convention and Mr. Garland was elected governor, and the Democrats have been in control of the state government from that time until the present day.

When I returned to Bentonville the last of May, 1874, I entered into a partnership to practice law with Judge R. W. Ellis. Judge Ellis was one of the most lovable men I ever knew, always good natured and good humored, and disposed to depreciate himself and to somewhat exaggerate the good qualities of his friends. We practiced together continually, having a very good practice, for four years, and then in September, 1878, I was elected judge of the circuit court. There were eight counties in the district and two terms of court each year in each county. Take it all in all, I think the four years I served as judge of the court were the most pleasant of all my public life, and I frequently afterwards regretted that I had not remained on the bench.

In June, 1882, I was nominated by the Democratic State Convention for governor of the state, and in the September following was elected over Mr. Slack, the Republican nominee, and Hon. R. K. Garland, who was a brother of United States Senator A. H. Garland, and nominee of the Greenback party, by a majority of 38,000, and entered upon the duties of the office in January, 1883. I served as governor from January, 1883, to January, 1885.

The term of United States Senator J.D. Walker expired on March 4th, 1885. I had refused to be a candidate for the second term as governor. I would have had no opposition if I had made the race, but the salary of the office was only $3,000 a year and the demands upon me were such that I simply was unable financially to continue in the office of governor. I had not only spent the salary for the two years I was there, but had spent $800 which I had saved out of my salary as judge, and had to borrow $200 to bring my family home from Little Rock.

Hon. James K. Jones and Poindexter Dunn, both members of Congress, and myself were candidates for the United States Senate to succeed Mr. Walker. After the Legislature had balloted for more than two weeks and no one was elected, our votes being about equal, I became satisfied that I could not be elected and so withdrew from the race while 38 of the members were still voting for me, and the next day Senator Jones was elected. A little more than two months afterwards, Mr. Garland, the other Senator from Arkansas, was appointed Attorney General of the United States in Mr. Cleveland’s cabinet, thereby leaving another vacancy in the Senate from Arkansas. Mr. Dunn, Major Horner, Joe House, Bob Newton and I were candidates for this vacancy before the Legislature, and on the fourth or fifth ballot I was elected to succeed Mr. Garland, whose term still had four years to run.

I was sworn into the Senate March 25th, 1885, and served there continuously for twenty-two years. At the expiration of the four years to which I was elected to succeed Mr. Garland I had no Democratic opposition for re-election and was elected for six years in January, 1889, At the expiration of that term, in January, 1895, I was again elected, over Gov. W. M. Fishback, and in January, 1901, I was elected for another term, over Gov. Dan W. Jones, and in January, 1907, I was defeated by Jeff Davis. I had been elected four times by the Legislature, although the first time was for four years only.

I remained out of office until the 17th of October, 1910, when, without solicitation on my part, and without my having ever written anyone in regard to it, I was appointed by the Secretary of War, upon the personal request of President Taft, to succeed Gen. William C. Oates, of Alabama, who had died in September, and who had been appointed by President Taft, when Secretary of War, as Commissioner to mark the graves of Confederate soldiers who died in Northern prisons during the war and were buried near the places where they had died. The law authorizing these appointments was passed in 1906. Col. Elliott, of South Carolina, had been first appointed, and at his death Gen. Oates was appointed to succeed him. Soon after my appointment the time for the completion of this work was extended until the 23rd of December, 1912. The work is now almost completed, and I expect to report to the Secretary of War very soon that the work is completed and that my services are no longer needed, and I think there will be left on the original appropriation an unexpended balance of about $40,000.

This is a brief statement of the principal events of my public and private life.

There have been born to my wife and myself six children. My oldest daughter, Nellie Frank Berry, was married to William H. Hyatt. She died the 11th of June, 1900, leaving two children, Berry Hyatt and William H. Hyatt Jr. At the time of her death they were eight and six years old respectively. We have raised them in our home, and the daughter, Berry, is now married to Mr. Henry Norton. Our daughter, Bert, married Mr. E. O. Lefors, and another daughter, Jennie, married Mr. A. P. Smartt. We had still another daughter, Bessie, who lived to be six years old. We have two sons, Elliott and Frederic, both of whom are living now.

This sketch has been written because I thought it might be some day be of interest to my children, and I want to say for their benefit that from the time I was elected to the Legislature in 1872 up to the present I have almost continuously in public life, and during that time I have never practised law, never entered into any kind of speculation, never rode on a free pass or accepted any other benefit, and have never made any money in any way except my salary and the mileage attached to the office.

I came out of the Senate about as poor as I went into it, and but for the fact that my wife had inherited some land and some other property from her father, we would have found much difficulty in providing for the necessities of life. I had been so long out of the practice of the law that I could not hope to make any great amount of money at my profession and I was not physically able to do manual labor. I think it would not be egotism if I say that during all the years of my public life I have never intentionally wronged the public or wronged any individual, and that I tried earnestly to serve the people faithfully in every way that I possibly could, and I am deeply indebted to the thousands of friends all over the state of Arkansas who have stood by me in every contest I have ever made. I love the state and her people and it is a gratification to me to know that I have never done a deed that brought shame or dishonor on the people who so often honored me.

I was born on a farm in Jackson County, Alabama, on May 15th 1841. My father was James M. Berry and my mother was Isabelle Jane Orr. In 1848, when I was seven and a half years old, I moved to Carrollton, Carroll County, Arkansas.

There were ten children of us who lived to be grown: Granville, the oldest; Mary, who married Col. Sam W. Peel; Fannie, who married Rufus Polk; Dick; and then I came next; then Arkansas, called “Canty,” who married Captain Arch McKennon; Willie who was killed during the war; Sophronia, who married Andrew Forrest; Albert; Emma, the youngest, who married Dr. A. M. McKennon. They are all dead except Sophronis Forrest and myself.

I was raised on a small farm adjoining the village of Carrolton. My father for a part of the time sold goods in the town and I attended the village school some time during the winter and learned to read and write a little, and something of arithmetic. When I was 17 years old my father sent me to the Berryville Academy 18 miles from our home, which was the best school in that locality, and I attended that school for 10 months.

In 1860 my mother died after a long illness, and the expenses attending her sickness forced my father to sell our home, and I was taken from the school and sent to Yellville, Arkansas, to clerk in the store of James H. Berry, who was a cousin of my father. I remained there until the war began, when I came back to our old home in Carrollton and joined the Confederate Army on the 19th of September, 1861. On the same day that I enlisted I was elected Second Lieutenant in what was afterwards Company E, Sixteenth Arkansas Infantry.

We went into winter quarters that winter at Elm Springs Arkansas, and remained there until February 1862, when we were sent to meet General Price, who was retreating from Missouri. He continued to retreat to the Boston Mountains in Arkansas, and early in March, 1862, General VanDorn took command and we went from there to Pea Ridge, Arkansas, where on the 7th and 8th of March we fought the battle called by the Union soldiers “Pea Ridge” and called "Elk Horn” by the Confederates. We were defeated, and retreated from Pea Ridge to the Arkansas River, and from there we went by way of Memphis to Corinth, Mississippi, where we joined General Beauregard’s army on about April 15th, 1862. A few days afterwards my regiment, being on outpost duty, became engaged and we lost 17 killed and wounded. The last of May General Beauregard evacuated Corinth and moved to Tupelo, Mississippi, and we remained at Tupelo and Satillo until September, when we went to Iuka, Mississippi.

On the 19th of September, 1862, one year from the day when I enlisted we fought the fight at Iuka. We went from Iuka and joined a portion of the army of VanDorn at Holly Springs, Mississippi, and on the 3rd and 4th of October, 1862, we fought the battle of Corinth, Mississippi. General VanDorn commanded the Confederate forces and General Rosencrans the Union Forces. We attacked their breastworks in a terrible engagement and the brigade to which I belonged, consisting of about 1500 or 1600 men, lost 402 men in less the 30 minutes. I was badly wounded, resulting in the loss of my right leg. I fell into the hands of the Federal Army and was sent to a hospital at Iuka, Mississippi. I remained in the hospital there for two months and was then taken to Rienzi, Mississippi, by a relative of mine – my father’s aunt. I remained there for several months and it was five months from the time I was wounded until I joined my regiment at Port Hudson, Louisiana.

While I was at a private house some 18 miles from Port Hudson, where I went to await for my brother-in-law, Lieut. McKennon, to try to get a furlough to take me home, Port Hudson became besieged by General Banks, leaving me on the outside. I remained there during the entire siege of 49 days. My younger brother, Willie, was at Port Hudson at the time, although he had been discharged from the army a few days before because he had served out the twelve months for which he had enlisted and, not being 18 years old, was not subject to military duty under the conscript law. When Banks surrounded the place he was on the inside of Port Hudson and, although not required to do so, he took his gun and went back into the Company.

When Port Hudson surrendered, all the privates, my brother amongst them, were paroled. Lieut McKennon, with the other officers, was taken to Johnson Island, Ohio. Two of the officers of my regiment, Capt. Poynor of my own Company and Lieut. Bailey of Company D, made their escape from Port Hudson after the surrender, and they came to the house where I was staying. My brother came with them and all of us together made our way back to Arkansas, crossing the Mississippi River in skiffs and traveling in various ways. Part of the time I rode a mule while they walked and we finally reached Little Rock, Arkansas. Capt. Poyner and Lieut. Bailey went from Little Rock across the mountain on foot to our old home in Carroll County, and my brother and I took a stage and came to Ozark, Arkansas, where my sister and father lived. We reached there in August, 1863, and stayed there for some two months, and from there I went back to our old home in Carroll County, staying with my sister, Mrs. Sam W. Peel, who was still living there. The country was in a very disturbed condition. There were quite a number of Confederate soldiers, some of them refugees from Missouri and some who had been paroled from the army at Port Hudson and at Vicksburg. Many of them were what were called “Independent Companies,” but no regular organized army was in the immediate section. The Federal soldiers came in from time to time and more or less fighting and skirmishing and killing was going on in the county.

I remained there as long as I dared, and then, with my sister, the wife of Lieut McKennon, crossed the mountain and went back to Ozark. While I was at Ozark the Fourteenth Kansas Cavalry, U.S.A., under Col. Brown, occupied the place. He required all the old men left at home to take the oath of allegiance to the Government, and sent for me and asked me to take the oath. I told him that I did not desire to take the oath of allegiance; that I was a Lieutenant in the Confederate Army; that I was a prisoner and that he had the right to send me to prison if he desired to do so, but that he had no right to require me to take the oath. He said that he did not wish to send a man to prison who had but one leg and was on crutches, but that he was under no obligations to protect me from the soldiers unless I did take the oath. I told him that I did not think the soldiers would hurt me and that I was willing to take it. He told me very curtly that I could retire. A few days after this he moved his regiment to Clarksville, Arkansas, 25 miles away, expecting to return, and the day the Federals left, Capt. McDonald of the Confederate Army, with some other Confederates, came into town.

McDonald told me that he and some 30 or 40 others were going south the next morning and that if I could get across the river that night and join them at daylight that he had an extra pony which I could ride and could go south with them. I managed to get an old man at 1 o’clock that night to set me across the river in a skiff and joined the soldiers on the other side and went with them to Monticello, Arkansas, where my old regiment was camped, reaching there in the fall of 1864. I remained at Monticello until February, 1865, and went from there to Shreveport, Louisiana, and then obtained a furlough from General Kirby Smith in person for 90 days.

I went from there to Texas and stayed with relatives in Tarrant and Ellis Counties until the first of May, when the Confederate Army west of the Mississippi disbanded. I was with General Cabell’s command at Corsicana when the soldiers broke up and went to their homes. I gave my watch, which my father had given me before the war for a horse and rode back to Ozark, reaching there about the 10th of June, 1865. I stayed with my sister and soon after began teaching a school, for three months, of some 30 children.

I had gotten acquainted, while in Ozark during the war, with Lizzie Quaile, whose father and mother lived there. Her father was still in Texas when I reached Ozark and did not get back until about September 1st. In the meantime I had seen her almost every day and we had promised each other that sometime in the future we would be married. When her father came home and learned of the situation, he informed her that he seriously objected to her marrying me, and that he proposed to send her off to Kentucky to school. She told me about it and I went and talked to him. He told me that he could not consent to the marriage; that I had no way to make a living; that he knew nothing against me, but that he was unwilling for his daughter to marry me because I had no means of support and no prospects. I told him that I was willing to wait a reasonable length of time, but that I would like for him to say that, if I could get along and make a living he would consent. He said there was no use in holding out hope in which in all probability could not be realized, and that we would have to give it up, and that he was going to send her to Kentucky to school. He then said he would like to know the course I proposed to pursue in regard to it. I told him that I had never asked her to marry me against his wishes, and that I did not know whether or not she would do so, but that she had told me that she did not wish to go to Kentucky to school, and that, rather than have her sent away against wishes, I would marry her if I could. He then said the only unkind words to me that he ever did say, and that was that I had better be careful. This was on Monday, and on Tuesday night at my aunt’s house we were married. We stayed with my sister for a few weeks and then went to Carrollton. I will say here that it was seventeen years from the time we married before Mr. Quaile and I spoke to each other. In 1882, the day after I was nominated for governor, I came from Little Rock to Ozark with Henry Carter, who had married my wife’s sister, and Gen. H. B. Armistead, a prominent man from Franklin county, and they urged me very earnestly that when we stopped off at Ozark that I should go to Mr. Quaile and offer him my hand. I told them that I was afraid he would not accept it, and they both said they were assured that he would do so. I thought the matter over and concluded that the time had come when I could go to him and that he could not very well come to me without having his motives misconstrued. In company with Henry Carter, I walked over to his house, and when he came out on the front porch I spoke to him and offered him my hand. He took my hand and asked me to walk into the house, and when he came out on the front porch I spoke to him and offered him my hand. He took my hand and asked me to walk into the house. I went in and we began to talk about the convention and the cotton crop, and never from that time until his death was the marriage mentioned between us. I want to say here that Mr. Quaile was a man of the very highest character, a splendid man in every way and respected wherever he was known. He was devoted to his family, and I never blamed him for objecting to the marriage. It was the most natural thing in the world that he should object, as I had absolutely nothing, not even a law license, and was on crutches. When I had daughters of my own I realized that, under the same conditions I would have done as he did.

After going back to Carrollton we lived for a time in a small house, about eight feet square, which had been built before the war for a milk house over the well. We ate with Col. Peel's family in a log house that he had built after the war, his house having been burned.

While I was teaching school at Ozark I had borrowed a law book wherever I could find one and was reading law, and I continued to read after I went back to Carrollton. On the first Monday in August, 1866, I was elected to the Legislature from Carroll county, being the youngest man in the Legislature. I was opposed in the race by four or five older men, but as two were to be elected, I was chosen as one of them. On my way to Little Rock I stopped over for a day in Ozark and secured my license to practice law. The session of the Legislature was a long one and the pay was six dollars a day, and that, together with the mileage, enabled me to save about three hundred dollars during the session. I went back to Carrollton after the adjournment and built a one-room log cabin, and we lived in that for two years. I went to work at such practice as I could get before the justice of the peace and the county court and occasionally in the circuit court. I also assisted the clerk of the court in his office at different times and made some money in that way.

In December, 1869, I sold my property at Carrollton and that, together with the money I had saved, enabled me to build a house at Bentonville, Ark., where we moved and where I have since lived. For a time after moving to Bentonville I practiced law in partnership with Col. S. W. Peel. In September, 1872, I was elected to the Legislature from Benton county. During the term for which I was elected, in May, 1874, what was known as the Brooks-Baxter war took place over the governorship of Arkansas and Governor Baxter called an extraordinary session of the Legislature, of which I was a member. The original Legislature was composed of a majority of Republicans, but numerous vacancies had occurred by reason of appointments to office, and these had been filled by Democrats. When the Legislature met, Mr. Tankersley speaker of the House, who was a Republican, had joined the Brooks side of the war then going on and did not appear in answer to the call of Governor Baxter. The majority of those being Democrats, we proceeded to remove Mr. Tankersley from the speakership and I was elected Speaker in his place. This extraordinary session of the Legislature while I was speaker called the constitutional convention and Mr. Garland was elected governor, and the Democrats have been in control of the state government from that time until the present day.

When I returned to Bentonville the last of May, 1874, I entered into a partnership to practice law with Judge R. W. Ellis. Judge Ellis was one of the most lovable men I ever knew, always good natured and good humored, and disposed to depreciate himself and to somewhat exaggerate the good qualities of his friends. We practiced together continually, having a very good practice, for four years, and then in September, 1878, I was elected judge of the circuit court. There were eight counties in the district and two terms of court each year in each county. Take it all in all, I think the four years I served as judge of the court were the most pleasant of all my public life, and I frequently afterwards regretted that I had not remained on the bench.

In June, 1882, I was nominated by the Democratic State Convention for governor of the state, and in the September following was elected over Mr. Slack, the Republican nominee, and Hon. R. K. Garland, who was a brother of United States Senator A. H. Garland, and nominee of the Greenback party, by a majority of 38,000, and entered upon the duties of the office in January, 1883. I served as governor from January, 1883, to January, 1885.

The term of United States Senator J.D. Walker expired on March 4th, 1885. I had refused to be a candidate for the second term as governor. I would have had no opposition if I had made the race, but the salary of the office was only $3,000 a year and the demands upon me were such that I simply was unable financially to continue in the office of governor. I had not only spent the salary for the two years I was there, but had spent $800 which I had saved out of my salary as judge, and had to borrow $200 to bring my family home from Little Rock.

Hon. James K. Jones and Poindexter Dunn, both members of Congress, and myself were candidates for the United States Senate to succeed Mr. Walker. After the Legislature had balloted for more than two weeks and no one was elected, our votes being about equal, I became satisfied that I could not be elected and so withdrew from the race while 38 of the members were still voting for me, and the next day Senator Jones was elected. A little more than two months afterwards, Mr. Garland, the other Senator from Arkansas, was appointed Attorney General of the United States in Mr. Cleveland’s cabinet, thereby leaving another vacancy in the Senate from Arkansas. Mr. Dunn, Major Horner, Joe House, Bob Newton and I were candidates for this vacancy before the Legislature, and on the fourth or fifth ballot I was elected to succeed Mr. Garland, whose term still had four years to run.

I was sworn into the Senate March 25th, 1885, and served there continuously for twenty-two years. At the expiration of the four years to which I was elected to succeed Mr. Garland I had no Democratic opposition for re-election and was elected for six years in January, 1889, At the expiration of that term, in January, 1895, I was again elected, over Gov. W. M. Fishback, and in January, 1901, I was elected for another term, over Gov. Dan W. Jones, and in January, 1907, I was defeated by Jeff Davis. I had been elected four times by the Legislature, although the first time was for four years only.

I remained out of office until the 17th of October, 1910, when, without solicitation on my part, and without my having ever written anyone in regard to it, I was appointed by the Secretary of War, upon the personal request of President Taft, to succeed Gen. William C. Oates, of Alabama, who had died in September, and who had been appointed by President Taft, when Secretary of War, as Commissioner to mark the graves of Confederate soldiers who died in Northern prisons during the war and were buried near the places where they had died. The law authorizing these appointments was passed in 1906. Col. Elliott, of South Carolina, had been first appointed, and at his death Gen. Oates was appointed to succeed him. Soon after my appointment the time for the completion of this work was extended until the 23rd of December, 1912. The work is now almost completed, and I expect to report to the Secretary of War very soon that the work is completed and that my services are no longer needed, and I think there will be left on the original appropriation an unexpended balance of about $40,000.

This is a brief statement of the principal events of my public and private life.

There have been born to my wife and myself six children. My oldest daughter, Nellie Frank Berry, was married to William H. Hyatt. She died the 11th of June, 1900, leaving two children, Berry Hyatt and William H. Hyatt Jr. At the time of her death they were eight and six years old respectively. We have raised them in our home, and the daughter, Berry, is now married to Mr. Henry Norton. Our daughter, Bert, married Mr. E. O. Lefors, and another daughter, Jennie, married Mr. A. P. Smartt. We had still another daughter, Bessie, who lived to be six years old. We have two sons, Elliott and Frederic, both of whom are living now.

This sketch has been written because I thought it might be some day be of interest to my children, and I want to say for their benefit that from the time I was elected to the Legislature in 1872 up to the present I have almost continuously in public life, and during that time I have never practised law, never entered into any kind of speculation, never rode on a free pass or accepted any other benefit, and have never made any money in any way except my salary and the mileage attached to the office.

I came out of the Senate about as poor as I went into it, and but for the fact that my wife had inherited some land and some other property from her father, we would have found much difficulty in providing for the necessities of life. I had been so long out of the practice of the law that I could not hope to make any great amount of money at my profession and I was not physically able to do manual labor. I think it would not be egotism if I say that during all the years of my public life I have never intentionally wronged the public or wronged any individual, and that I tried earnestly to serve the people faithfully in every way that I possibly could, and I am deeply indebted to the thousands of friends all over the state of Arkansas who have stood by me in every contest I have ever made. I love the state and her people and it is a gratification to me to know that I have never done a deed that brought shame or dishonor on the people who so often honored me.