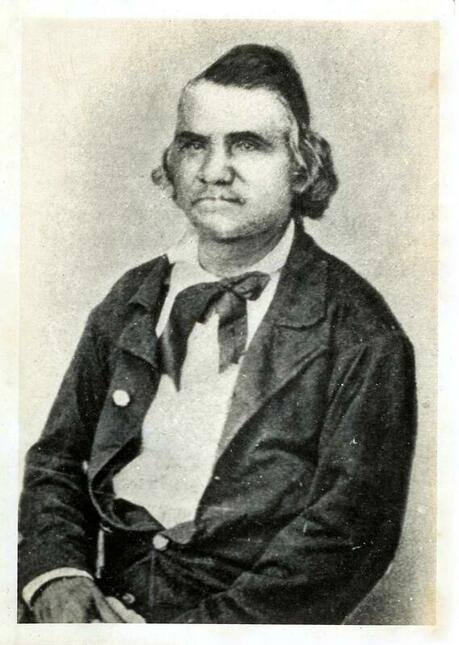

Brigadier General Stand Watie

By Billie Jines (Pea Ridge Graphic, 1966)

By Billie Jines (Pea Ridge Graphic, 1966)

In 1868, a student at the Cane Hill College wrote a letter to his father, and, as letters from college students to their parents go, he was asking for some money, "foure dollars if you please, for I am ner without a hat..."

His name was Waticia Watie. Three years later, a letter preserved by the Arkansas Historical Quarterly from Waticia's sister, Jacqueline, a student at a Berryville School, sounded no differently.

"Papa, you must send me some money if it is not but $5 for I need it very bad, but if you have $25 send it for it will take that much to fix me up for the exhibition and more too I expect..."

Witicia had died in 1869, the year after he wrote the letter, and Jacqueline was to die in 1873, as was her sister. Their older brother, Saladin, had died in 1868, and their father, historically-famous Stand Watie, was destined to die the same year Jacqueline wrote the above letter.

Thus passed out of existence the last remnants of the family of a Cherokee of our area, who was bound to find a niche in our history books for several reasons.

In the first place, Stand Watie was one of the four Cherokees marked for murder as a result of their signing of the treaty that brought their tribe over the ill-fated Trail of Tears in 1835. Watie was the only one of the four who escaped. You may recall a recent column concerning one of the four, Major Ridge, who was murdered here in Arkansas near Dutch Mills.

As a result of the enmity that brought about the murders, Stand Watie, himself, was to stand trial for killing James Foreman in Benton County in 1842. The trial was held in Benton County Circuit Court May 15, 1843, and as a result of the eloquence of Watie's attorney, Alfred W. Arrington, Watie was aquitted. Arrington opened the defense by showing that Watie had been marked for death by the conspirators who killed the other three main signers of the treaty. He showed that Watie would have been justified in killing Foreman in self-defense in 1842, three years after the triple assassination. It took the jury only five minutes to agree.

Today, one of the streets of Pea Ridge is named for Stand Watie. Its naming had nothing to do with the Cherokee's part in the great removal of the tribe, but, rather, is directly connected with Watie's part in the Battle of Pea Ridge. All of the streets of Pea Ridge are named for officers, who fought in the Civil War Battle of Pea Ridge. The north-south streets bear the names of Union officers, while the east-west streets are named for Confederate officers. So it is that the North and the South meet on every corner in Pea Ridge.

His name was Waticia Watie. Three years later, a letter preserved by the Arkansas Historical Quarterly from Waticia's sister, Jacqueline, a student at a Berryville School, sounded no differently.

"Papa, you must send me some money if it is not but $5 for I need it very bad, but if you have $25 send it for it will take that much to fix me up for the exhibition and more too I expect..."

Witicia had died in 1869, the year after he wrote the letter, and Jacqueline was to die in 1873, as was her sister. Their older brother, Saladin, had died in 1868, and their father, historically-famous Stand Watie, was destined to die the same year Jacqueline wrote the above letter.

Thus passed out of existence the last remnants of the family of a Cherokee of our area, who was bound to find a niche in our history books for several reasons.

In the first place, Stand Watie was one of the four Cherokees marked for murder as a result of their signing of the treaty that brought their tribe over the ill-fated Trail of Tears in 1835. Watie was the only one of the four who escaped. You may recall a recent column concerning one of the four, Major Ridge, who was murdered here in Arkansas near Dutch Mills.

As a result of the enmity that brought about the murders, Stand Watie, himself, was to stand trial for killing James Foreman in Benton County in 1842. The trial was held in Benton County Circuit Court May 15, 1843, and as a result of the eloquence of Watie's attorney, Alfred W. Arrington, Watie was aquitted. Arrington opened the defense by showing that Watie had been marked for death by the conspirators who killed the other three main signers of the treaty. He showed that Watie would have been justified in killing Foreman in self-defense in 1842, three years after the triple assassination. It took the jury only five minutes to agree.

Today, one of the streets of Pea Ridge is named for Stand Watie. Its naming had nothing to do with the Cherokee's part in the great removal of the tribe, but, rather, is directly connected with Watie's part in the Battle of Pea Ridge. All of the streets of Pea Ridge are named for officers, who fought in the Civil War Battle of Pea Ridge. The north-south streets bear the names of Union officers, while the east-west streets are named for Confederate officers. So it is that the North and the South meet on every corner in Pea Ridge.

Brigadier General Stand Watie

Actually, Stand Watie's role in the Civil War may be thought of first and foremost in connection with the Battle of Pea Ridge, where Albert Pike commanded the Indian fighters, but Watie also earned a name for himself for other reasons, during the Great Conflict. He was the only Indian to become a brigadier general in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, and he was the last general to surrender after the war was over.

Stand Watie was born near Rome, Ga. Dec. 12, 1806. His name was Oo-too-ge-lo-gi, meaning, in English interpretation, Oowatie. His given name was Degataga, or "standing together." Thus, the shortened version became Stand Watie. His father was pure Cherokee. His mother was the daughter of a White man and a Cherokee mother.

Material sent for this column from the files of the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, says that Watie's first wife had died in childbirth, as had the child, before the tribe started its long trek to what is now Oklahoma.

Watie, who had been educated at a mission school in Tennessee, became a man of ability and, prior to the war, had been the owner of many slaves.

A few days prior to the Battle of Pea Ridge, Brig. Gen. Albert Pike had started in that general direction from the Cherokee Nation with as many Indian soldiers as he had been able to persuade to march without first being paid. It took three days to pay off the Choctaws and the Chickasaws, but, as by their treaties, they could not be taken out of Indian country without their consent.

In his official report, Pike wrote, "On the morning of the third day, I left them behind at Fort Gibson, except O. G. Welch's squadron of Texans, part of the First Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment, whom I persuaded to move by the promise that they should be paid at the Illinois River, I marched to Park Hill, near that River, remained there one day, and not being overtaken, as I had expected to be by the Choctaw and Chickasaw troops, moved the next day, Monday, March 3, towards Evansville, and the next day to Cincinnati, on the Cherokee line, where I overtook Col. Stand Watie's regiment of Cherokees."

And so the Indian troops who saw action in the Battle of Pea Ridge, marched toward that location and that great struggle. Stand Watie was leading what had been the first Cherokee regiment organized during the war, and Pike was commanding the entire Confederate Battalion of Indians. The Indians caused trouble during the battle. They were reluctant to fight against the Artillery of the Federals, and, too, some were accused of savagery, including some scalping, during the battle.

Goodspeed's History of Northwest Arkansas (1889) says: "Col. Stand Watie, with his Cherokee regiment, retreated to Bentonville during the second day of the fight."

It may never be known weather Stand Watie's reasons for being so long in surrendering after Lee's surrender at Appomattox (about six weeks elapsed before Watie's surrender) was because he didn't know the war was over or whether he just wanted to get as much revenge as possible.

After the war, he returned to his farm on Honey Creek not far from Southwest City, Mo. Watie, who had owned many slaves before the war and had been a man of wealth, was now so poor that historians say he couldn't send his little daughter to school because she had no shoes. But he was determined to see that his children got an education. So it was that in 1868- three years after the war - he managed to send Waticia to the Cane Hill College, and later to send Jacqueline to the Clark's Academy in Berryville, Minnehaha Watie attended Belle Grove Seminary in Fort Smith.

Since all of Stand Watie's children were dead within two years after his own death, no descendants of the widely-known Cherokee leader and Confederate general were left.

Watie's grave may be seen just outside the Arkansas-Missouri line in the Polson Cemetery. The small, well-kept cemetery is two and one-half miles west of Southwest City, Mo., in the edge of what is today Oklahoma.

Stand Watie was born near Rome, Ga. Dec. 12, 1806. His name was Oo-too-ge-lo-gi, meaning, in English interpretation, Oowatie. His given name was Degataga, or "standing together." Thus, the shortened version became Stand Watie. His father was pure Cherokee. His mother was the daughter of a White man and a Cherokee mother.

Material sent for this column from the files of the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, says that Watie's first wife had died in childbirth, as had the child, before the tribe started its long trek to what is now Oklahoma.

Watie, who had been educated at a mission school in Tennessee, became a man of ability and, prior to the war, had been the owner of many slaves.

A few days prior to the Battle of Pea Ridge, Brig. Gen. Albert Pike had started in that general direction from the Cherokee Nation with as many Indian soldiers as he had been able to persuade to march without first being paid. It took three days to pay off the Choctaws and the Chickasaws, but, as by their treaties, they could not be taken out of Indian country without their consent.

In his official report, Pike wrote, "On the morning of the third day, I left them behind at Fort Gibson, except O. G. Welch's squadron of Texans, part of the First Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment, whom I persuaded to move by the promise that they should be paid at the Illinois River, I marched to Park Hill, near that River, remained there one day, and not being overtaken, as I had expected to be by the Choctaw and Chickasaw troops, moved the next day, Monday, March 3, towards Evansville, and the next day to Cincinnati, on the Cherokee line, where I overtook Col. Stand Watie's regiment of Cherokees."

And so the Indian troops who saw action in the Battle of Pea Ridge, marched toward that location and that great struggle. Stand Watie was leading what had been the first Cherokee regiment organized during the war, and Pike was commanding the entire Confederate Battalion of Indians. The Indians caused trouble during the battle. They were reluctant to fight against the Artillery of the Federals, and, too, some were accused of savagery, including some scalping, during the battle.

Goodspeed's History of Northwest Arkansas (1889) says: "Col. Stand Watie, with his Cherokee regiment, retreated to Bentonville during the second day of the fight."

It may never be known weather Stand Watie's reasons for being so long in surrendering after Lee's surrender at Appomattox (about six weeks elapsed before Watie's surrender) was because he didn't know the war was over or whether he just wanted to get as much revenge as possible.

After the war, he returned to his farm on Honey Creek not far from Southwest City, Mo. Watie, who had owned many slaves before the war and had been a man of wealth, was now so poor that historians say he couldn't send his little daughter to school because she had no shoes. But he was determined to see that his children got an education. So it was that in 1868- three years after the war - he managed to send Waticia to the Cane Hill College, and later to send Jacqueline to the Clark's Academy in Berryville, Minnehaha Watie attended Belle Grove Seminary in Fort Smith.

Since all of Stand Watie's children were dead within two years after his own death, no descendants of the widely-known Cherokee leader and Confederate general were left.

Watie's grave may be seen just outside the Arkansas-Missouri line in the Polson Cemetery. The small, well-kept cemetery is two and one-half miles west of Southwest City, Mo., in the edge of what is today Oklahoma.