Building The Frisco Roadbed To Rogers

By J. Dickson Black

By J. Dickson Black

The Lebanon Construction Company of Lebanon, Mo. had the contract to build the grade for the Frisco railbed from Pierce City, Mo. to Fort Smith, Ark. They began work in the spring of 1880 and finished in 1882.

The company was made up of three partners: Edw. J. Burgess, Dan Faulkner, a lumberman from Bolivar, Mo. and Nathan Diffenderfer, a banker from Lebanon, Mo. Each of the men had a teenage son who spent their summers working at a grade camp.

One of the boys, W. W. Burgess, wrote a very interesting article about his summer work at the grade camps. I have used just the parts telling of his work leading to, or around Rogers.

In the summer of 1880 he was just 17, when he left Pierce City, Mo. with his father in a livery behind a spirited team of bays, bound for the construction camp southwest of Cassville close to the border of Arkansas.

At the camp there were tents for the three partners, the bookkeepers and the commissary clerk. The three boys had to make their beds on the hard counters with but one blanket under them. The commissary was housed in a long rambling structure of rough lumber. One end was closed off for the company office, where three bookkeepers kept the accounts for approximately 500 men.

The largest space was the commissary. The far end was the tool and powder house, which sheltered the tools, cans of black powder, and cases of dynamite and fuses. The caps for exploding the dynamite were always carried in the company safe so they would be handled with care. Yet many dynamite men clamped the caps on to the fuse by biting them with their teeth.

The company was made up of three partners: Edw. J. Burgess, Dan Faulkner, a lumberman from Bolivar, Mo. and Nathan Diffenderfer, a banker from Lebanon, Mo. Each of the men had a teenage son who spent their summers working at a grade camp.

One of the boys, W. W. Burgess, wrote a very interesting article about his summer work at the grade camps. I have used just the parts telling of his work leading to, or around Rogers.

In the summer of 1880 he was just 17, when he left Pierce City, Mo. with his father in a livery behind a spirited team of bays, bound for the construction camp southwest of Cassville close to the border of Arkansas.

At the camp there were tents for the three partners, the bookkeepers and the commissary clerk. The three boys had to make their beds on the hard counters with but one blanket under them. The commissary was housed in a long rambling structure of rough lumber. One end was closed off for the company office, where three bookkeepers kept the accounts for approximately 500 men.

The largest space was the commissary. The far end was the tool and powder house, which sheltered the tools, cans of black powder, and cases of dynamite and fuses. The caps for exploding the dynamite were always carried in the company safe so they would be handled with care. Yet many dynamite men clamped the caps on to the fuse by biting them with their teeth.

Stereoview taken of the Avoca Trestle near Rogers, Arkansas. The photo was taken in the 1880s when they were working on the St. Louis and San Francisco. It it appears they built a trestle and are filling around it with dirt.

The commissary carried provisions and supplies required by the various boarding houses. These were mostly run independently, often by foremen's wives and only occasionally by the company. They were scattered along the line or work, all in tents. The commissary carried such items as overalls, jumpers, heavy shoes, tobacco, and large red or blue handkerchiefs worn around the neck for ornamental purposes. There were pipes, knives and incidentals for the workmen's use, the commissary also carried numerous items for native use, bright colored calicos and ribbons, and a "Dipping snuff" which was used by a few of the older women in the area.

Company commissary money was issued to the workmen and boarding-house keepers to minimize bookkeeping. This money was often accepted from the boarding-house keepers by the hill people in exchange for their eggs and other products on their farms. The company money was printed on small varicolored cards, distinctive of the amounts ranging from 5 cents to $1, and was exchangeable only at the commissary for merchandise.

Time was figured for a ten hour day for all classes of employees. No time was allowed for less than one-fourth day, or two and a half hours. Time-keepers books read one-forth, one-half, three-fourths and one day. If a man was 10 minutes late he had to go to work at once but was only paid for three-fourths of a day. These hours and methods were uniform with all contractors and prevailed for all the work from Pierce City to Ft. Smith. Common labor was paid a $1.50 per day, semi-skilled $1.50, foremen $3 per day. A team was paid the same as a common laborer.

Board including sleeping quarters was $3.50 per week. Payment for the month was made the 20th of the following month. If discharged, the employee was given a time check (marked not transferable) due the following 20th of the month. These methods were planned to discourage the worker's quitting.

We were just across the Arkansas line when one day as I was standing outside the cashier's window in the office section of the commissary building, an elderly hill man approached carrying a rifle, he shoved it through the window and pointed it at the nearest bookkeeper and demanded immediate payment for some work performed on the grade. It seemed that the previous day he had made this request and was told to come back the 20th of the following month, as that would be his pay-day. He had returned to demonstrate that the company's "immovable" rule regarding payment could in this instance be set aside, and it was.

Company commissary money was issued to the workmen and boarding-house keepers to minimize bookkeeping. This money was often accepted from the boarding-house keepers by the hill people in exchange for their eggs and other products on their farms. The company money was printed on small varicolored cards, distinctive of the amounts ranging from 5 cents to $1, and was exchangeable only at the commissary for merchandise.

Time was figured for a ten hour day for all classes of employees. No time was allowed for less than one-fourth day, or two and a half hours. Time-keepers books read one-forth, one-half, three-fourths and one day. If a man was 10 minutes late he had to go to work at once but was only paid for three-fourths of a day. These hours and methods were uniform with all contractors and prevailed for all the work from Pierce City to Ft. Smith. Common labor was paid a $1.50 per day, semi-skilled $1.50, foremen $3 per day. A team was paid the same as a common laborer.

Board including sleeping quarters was $3.50 per week. Payment for the month was made the 20th of the following month. If discharged, the employee was given a time check (marked not transferable) due the following 20th of the month. These methods were planned to discourage the worker's quitting.

We were just across the Arkansas line when one day as I was standing outside the cashier's window in the office section of the commissary building, an elderly hill man approached carrying a rifle, he shoved it through the window and pointed it at the nearest bookkeeper and demanded immediate payment for some work performed on the grade. It seemed that the previous day he had made this request and was told to come back the 20th of the following month, as that would be his pay-day. He had returned to demonstrate that the company's "immovable" rule regarding payment could in this instance be set aside, and it was.

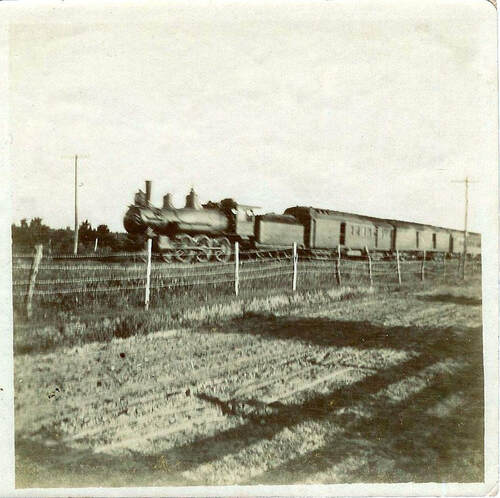

Cannon Ball Train - Frisco - Rogers, Arkansas

Young Burgess said that the typical home in the area was a small log cabin built on a hillside, not distant from a gushing spring that came from the cavernous mouth formed by shelving rocks where the family could also keep the milk and butter to be cooled. On the front porch was a spinning wheel. The "Click, Clack" of the family loom was almost always heard coming from a rear lean-to, where they wove cotton and wool for almost all of the family's garments.

A wood-ash receiver through which seeped water to form amber lye, which with animal fats made the family soap was built in the rear of the cabin.

The small clearing surrounding the cabin, with its larger plot for corn, smaller for cotton and tobacco and vegetables. There was a shed for the horse and cow, and three or four sheep. Roots and herbs from the nearby forest furnished most of their medicines.

Many covered wagons passed their camp on the way to Eureka Springs with sick people sure they would be cured of their ailments by the wonder water there that could cure anything short of a missing limb.

During his second year young Burgess was at a camp in Washington County called West Fork. He and his cousin Tom were sent back to Rogers with 25 men to do the grading for the roundhouse and shops. Since they had heard so much about Cross Hollows and the whiskey sold there they road ahead, of this he said:

"Upon reaching the Hollow we were mystified to discover nothing but a small structure of rough boards possibly 15 x 20 feet, a little distance from the main road. Hitching our horses we entered and found two men, evidently the operators, who voiced no greeting, but one of them pointed to one corner of the room, otherwise vacant, in which stood a large barrel (about 50 gallons), open topped and filled with moonshine whiskey to within a foot of the barrel rim. Hanging from a nail on the wall and suspended by a string, dangled a large tin cup. A piece of paper tacked to the wall bore the inscription "Drink all you want for 5 cents". We tasted the liquor merely, and left after paying a nickel. The drink was too rough for us," said Burgess.

A wood-ash receiver through which seeped water to form amber lye, which with animal fats made the family soap was built in the rear of the cabin.

The small clearing surrounding the cabin, with its larger plot for corn, smaller for cotton and tobacco and vegetables. There was a shed for the horse and cow, and three or four sheep. Roots and herbs from the nearby forest furnished most of their medicines.

Many covered wagons passed their camp on the way to Eureka Springs with sick people sure they would be cured of their ailments by the wonder water there that could cure anything short of a missing limb.

During his second year young Burgess was at a camp in Washington County called West Fork. He and his cousin Tom were sent back to Rogers with 25 men to do the grading for the roundhouse and shops. Since they had heard so much about Cross Hollows and the whiskey sold there they road ahead, of this he said:

"Upon reaching the Hollow we were mystified to discover nothing but a small structure of rough boards possibly 15 x 20 feet, a little distance from the main road. Hitching our horses we entered and found two men, evidently the operators, who voiced no greeting, but one of them pointed to one corner of the room, otherwise vacant, in which stood a large barrel (about 50 gallons), open topped and filled with moonshine whiskey to within a foot of the barrel rim. Hanging from a nail on the wall and suspended by a string, dangled a large tin cup. A piece of paper tacked to the wall bore the inscription "Drink all you want for 5 cents". We tasted the liquor merely, and left after paying a nickel. The drink was too rough for us," said Burgess.