The question of whether Benton County should be able to sell liquor has been going on for has been going on the better part of 200 years. While Arkansas was still a territory, a grand jury was impaneled to try to invoke an outdated law that would prevent the production and sale of alcohol, but the law was never enforced. During these early times prior to the Civil War, laws weren't abided by and corruption ran wild in the state.

People in Arkansas had growing concerns around the alcohol-related unrest that seemed to happen around drinking establishments of that day. Even as early as 1831, a temperance society was formed was formed in Little Rock. The original movement advocated against whiskey and hard liquor while quietly approving consumption of wine and beer. In 1850, the Arkansas General Assembly moved to ban the production and sale of alcohol, but this law did little to stop the production and consumption of alcohol. In 1855, the state enabled counties and cities to decide on their own prohibition. This early movement had strong support from women, African-Americans, and local churches.

After the Civil War, the temperance movement picked up in the state. In 1885, a law was passed that made it illegal for saloons to be open on Sunday. A few years after that, a law was passed that allowed children to buy alcohol for their parent as long as they had written permission. By 1899, a law was passed that made it illegal to buy alcohol for someone else. At this time there seem to be a saloon on every corner.

People in Arkansas had growing concerns around the alcohol-related unrest that seemed to happen around drinking establishments of that day. Even as early as 1831, a temperance society was formed was formed in Little Rock. The original movement advocated against whiskey and hard liquor while quietly approving consumption of wine and beer. In 1850, the Arkansas General Assembly moved to ban the production and sale of alcohol, but this law did little to stop the production and consumption of alcohol. In 1855, the state enabled counties and cities to decide on their own prohibition. This early movement had strong support from women, African-Americans, and local churches.

After the Civil War, the temperance movement picked up in the state. In 1885, a law was passed that made it illegal for saloons to be open on Sunday. A few years after that, a law was passed that allowed children to buy alcohol for their parent as long as they had written permission. By 1899, a law was passed that made it illegal to buy alcohol for someone else. At this time there seem to be a saloon on every corner.

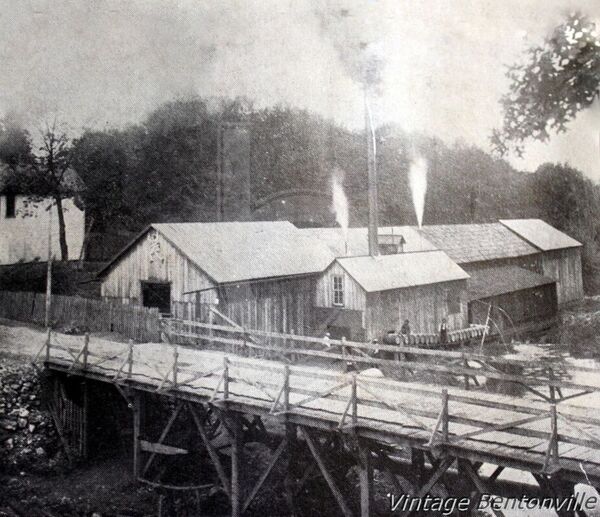

This is an image of the Mason & Carson Distillery in Bentonville, the largest apple brandy distillery west of the Mississippi.

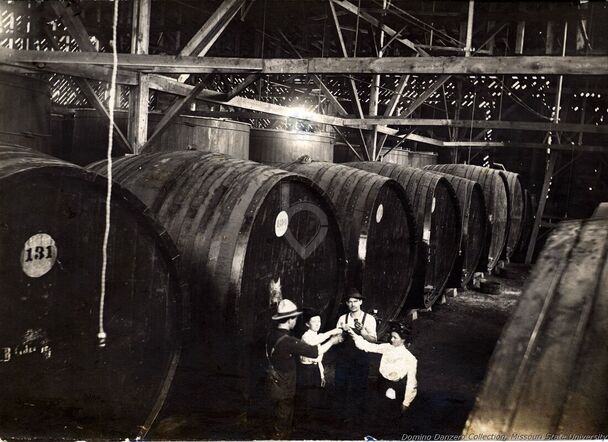

This is believed to be a photo at The Benton County Apple Brandy Company in Rogers.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the northwest area had 47 brandy and vinegar distilleries. Some of the better known distilleries in the area were the Mason & Carson Apple Brand Distillery in Bentonville, The Benton County Apple Brandy Company in Rogers, and the Vinola Wine Ranch at Monte Ne. There was a move in the late 1800's to prohibit the sale of alcohol.

In 1894, the counties in Arkansas were given the right to decide whether to become dry or wet counties. At that time, Benton County voted to become dry which meant there were to be no alcohol sales in the county. Every year from 1894 to 1914, the county would vote on whether to stay dry or become wet again. In the 1900 vote, the county initial tally showed that the county wanted to become wet again, but the election commission demanded a recount in the the votes. The county remained dry by 11 votes.

In the early 1900s, the Benton County judge said, "There will be no saloons in Benton County while I am judge." During this time the local distilleries were still making brandy and wine and selling them outside the county. With no saloons in Benton County, the moonshine business real took. Alcohol was readily available for anyone who wanted it.

By 1914, only nine counties in the state could still sell alcohol. In 1915, the General Assembly of the state of Arkansas passed a law banning the sale of alcohol in the state. The national prohibition was put into place in the 1920. Although the law in theory stopped the making of alcohol, the law didn't stop the consumption of alcohol.

In 1894, the counties in Arkansas were given the right to decide whether to become dry or wet counties. At that time, Benton County voted to become dry which meant there were to be no alcohol sales in the county. Every year from 1894 to 1914, the county would vote on whether to stay dry or become wet again. In the 1900 vote, the county initial tally showed that the county wanted to become wet again, but the election commission demanded a recount in the the votes. The county remained dry by 11 votes.

In the early 1900s, the Benton County judge said, "There will be no saloons in Benton County while I am judge." During this time the local distilleries were still making brandy and wine and selling them outside the county. With no saloons in Benton County, the moonshine business real took. Alcohol was readily available for anyone who wanted it.

By 1914, only nine counties in the state could still sell alcohol. In 1915, the General Assembly of the state of Arkansas passed a law banning the sale of alcohol in the state. The national prohibition was put into place in the 1920. Although the law in theory stopped the making of alcohol, the law didn't stop the consumption of alcohol.

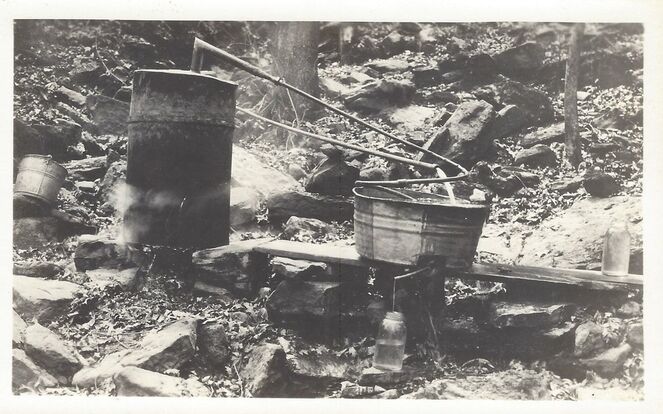

This is one of the moonshine stills that would be found in the area at that time.

In the 1920s, the moonshine business grew as a backwoods industry. Moonshiners would set up their stills in forests, caves, or by springs. They could take some basic ingredients (often corn, sugar, and yeast) and turn it into corn whiskey that would sell for 20 to 50 times the cost of the ingredients. During this time came "speakeasies" or "blind tigers" popped up. These were places you could drop money in a door and, in a few minutes, the money was gone and a mason jar of moonshine was found in its place. Moonshiners were always on the lookout for the lawmen who would arrest them and destroy their stills.

This became a time of what many regarded to be lawlessness and moral decay in our country. A common belief was that morality couldn't be legislated by the government but needed to be taught in the home. Whatever the case, by the early 1930s, there arose a movement to repeal the prohibition laws.

This became a time of what many regarded to be lawlessness and moral decay in our country. A common belief was that morality couldn't be legislated by the government but needed to be taught in the home. Whatever the case, by the early 1930s, there arose a movement to repeal the prohibition laws.

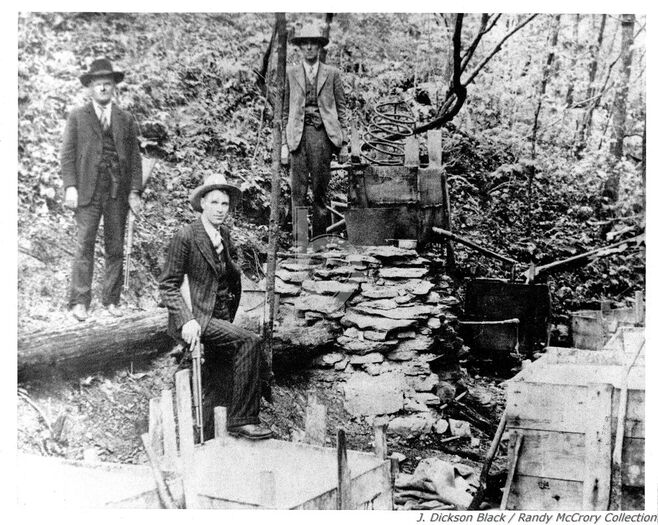

This whiskey still was found north of Bentonville near the Missouri and Arkansas line in the 1920s.

In the photo from left to right are: Special Agent Willie Graham; Sheriff Joe Gailey; Chief Deputy Edgar Fields.

At that time many stills were found every year in the county.

In the photo from left to right are: Special Agent Willie Graham; Sheriff Joe Gailey; Chief Deputy Edgar Fields.

At that time many stills were found every year in the county.

In 1932, Joseph T. Robinson was re-elected as the senator of Arkansas. Mr. Robinson was never a supporter of prohibition, but the country's mood by this time had softened on the subject. Mr. Robinson helped to draft legislation that repealed the Eighteenth Amendment to allow the sale of alcohol again. That made the whole country wet again in theory, but Arkansas still allowed counties to decide whether to be dry or a wet. In the 1933 vote, Benton County decided to stay dry.

In late 1944, the vote to stay a dry county was close, with only a 90 vote difference. People who supported liquor sales said this election wasn't fair because of so many service members who had not yet returned home, so a second election was held a month later. This time John Brown of John Brown University jumped in to support keeping the county dry. He said, "...if the manufacturer, and the seller, and the buyer of liquor go to hell, so much the voter who supports the wets. A vote for the wets is a sure and certain ticket to hell." In this special election, the county stayed dry by a 2 to 1 vote.

Benton County stayed dry until a 2003 vote which allowed alcohol to be served in clubs. In 2012, the country voted to go wet, due largely to the influx of people who have moved here from others states.

In late 1944, the vote to stay a dry county was close, with only a 90 vote difference. People who supported liquor sales said this election wasn't fair because of so many service members who had not yet returned home, so a second election was held a month later. This time John Brown of John Brown University jumped in to support keeping the county dry. He said, "...if the manufacturer, and the seller, and the buyer of liquor go to hell, so much the voter who supports the wets. A vote for the wets is a sure and certain ticket to hell." In this special election, the county stayed dry by a 2 to 1 vote.

Benton County stayed dry until a 2003 vote which allowed alcohol to be served in clubs. In 2012, the country voted to go wet, due largely to the influx of people who have moved here from others states.