The Story of "Coin" Harvey, Part 1

Story from a brochure printed by the Harvey House Steak House by Mr. and Mrs. W. T. McWorter (1960)

Story from a brochure printed by the Harvey House Steak House by Mr. and Mrs. W. T. McWorter (1960)

Not too long ago a political group was hatched in the Ozarks - at Benton county's Monte Ne - and a ticket put on the ballot which received votes from every state in the Union. It happened only 28 years ago - seven campaigns ago [as of the article's writing]. The man who ran on the Arkansas-spawned ticket won only a small percentage of the votes, but he made a splash over the nation just the same.

He was Coin Harvey, the Sage of Monte Ne, a man who made and lost a fortune and accomplished and failed in more projects than any hundred ordinary men. He was the kind of individual around whom legends grow surely as the sun shines and the rain falls.

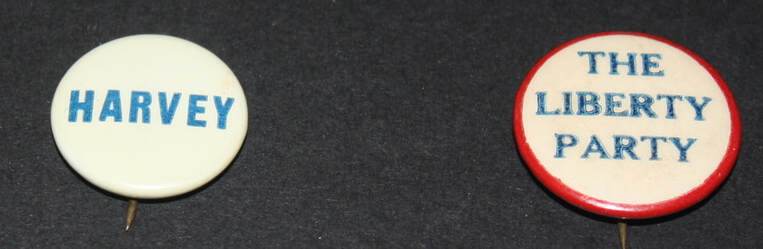

But back to the subject of the "third party." The flegling organization, which sincerely hoped to put Harvey in the White House in 1933, was named the Liberty Party. Its catch phrase was "Prosperity in Ninety Days." The official newspaper, the Libery Bell, edited by Harvey, called for a "Second Declaration of Independence" and boldly stated seven resolutions from the party platform which it flatly called the remedy for all that ailed the sickly economic life of the time.

When time for the Liberty Party's convention rolled around, railroads all over the country slapped on excursion rates to the backwoods village of Monte Ne. At Rogers elaborate plans were made to take care of the great throng of delegates and visitors - 10,000 were expected - which would overflow the tiny neighboring community. When a heavy downpout washed out the road between the towns, Rogers business men got jittery when they pictured thousands of motorists stalled, unable to get to the convention site, and ranting about Benton county roads. A grading crew was put on the job and got the road back in shape in record time. Then all Northwest Arkansas settled down to experience the headaches - and the good publicity - of a national political conclave.

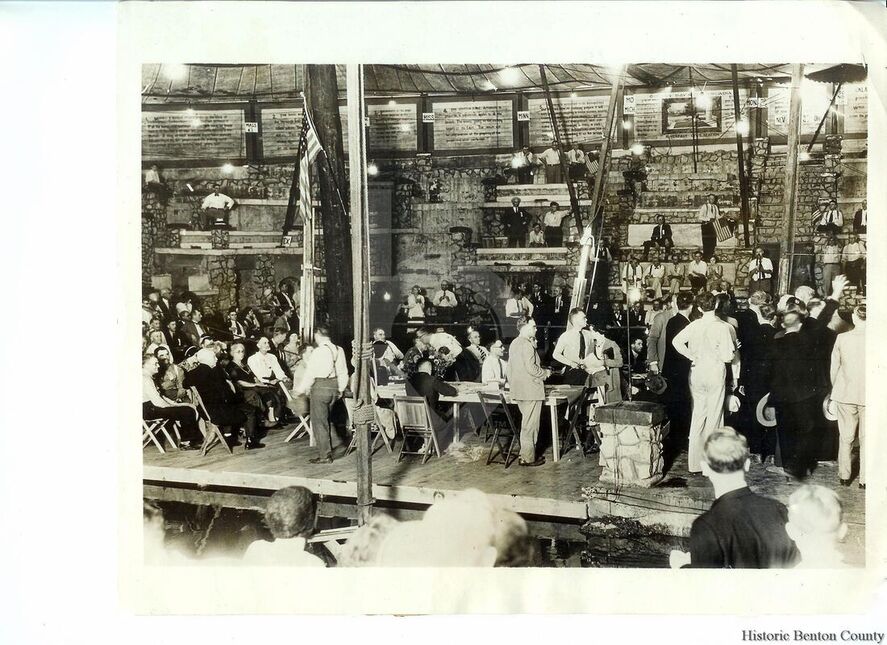

But when the long awaited convention was finally called to order at the amphiteater - which was about all that had been built of Harvey's world-famous pyramid project - the number present was disappointing to say the least. When the roll was called there were only 786 delegates on hand. But they stood and cheered loudly as the 80-year-old Harvey faced the loudspeaker mikes which were to carry his voice out over the crowd, the amphitheatre and the tree-shadowed lagoon nearby.

He was Coin Harvey, the Sage of Monte Ne, a man who made and lost a fortune and accomplished and failed in more projects than any hundred ordinary men. He was the kind of individual around whom legends grow surely as the sun shines and the rain falls.

But back to the subject of the "third party." The flegling organization, which sincerely hoped to put Harvey in the White House in 1933, was named the Liberty Party. Its catch phrase was "Prosperity in Ninety Days." The official newspaper, the Libery Bell, edited by Harvey, called for a "Second Declaration of Independence" and boldly stated seven resolutions from the party platform which it flatly called the remedy for all that ailed the sickly economic life of the time.

When time for the Liberty Party's convention rolled around, railroads all over the country slapped on excursion rates to the backwoods village of Monte Ne. At Rogers elaborate plans were made to take care of the great throng of delegates and visitors - 10,000 were expected - which would overflow the tiny neighboring community. When a heavy downpout washed out the road between the towns, Rogers business men got jittery when they pictured thousands of motorists stalled, unable to get to the convention site, and ranting about Benton county roads. A grading crew was put on the job and got the road back in shape in record time. Then all Northwest Arkansas settled down to experience the headaches - and the good publicity - of a national political conclave.

But when the long awaited convention was finally called to order at the amphiteater - which was about all that had been built of Harvey's world-famous pyramid project - the number present was disappointing to say the least. When the roll was called there were only 786 delegates on hand. But they stood and cheered loudly as the 80-year-old Harvey faced the loudspeaker mikes which were to carry his voice out over the crowd, the amphitheatre and the tree-shadowed lagoon nearby.

Photo of the Libery Party Convention at the amphitheater at Monte Ne

There surely never was another political convention held in such a clean and idyllic spot. There was no chance for smoke filled rooms here. Erect, defiant and at the same time strangely impersonal, Harvey pleded the good fight for the ideals as the party - ideals which really were his own ideals as the party was his own creation.

The delegates nominated the aged Coin Harvey for the nation's highest office and then drifted back to their homes in 25 states. Remaining at Monte Ne, which was more than ever now one of the most publicized villages in the world, Harvey and his associates got busy pushing the campaign. Along with his secretary-wife and C. W. Henninger, party chairman, he settled down to some old-fashioned journalistic tom-tom beating in the pages of The Liberty Bell. This paper, mailed throughout the United States, became the Bible of the Harvey followers. The whole Liberty Party campaign was waged with the fervor of red-hot evangelism.

But in November the mass movement of voters to Governor Roosevelt's standard must have stamped a great many good Liberty Party people into the Democratic camp. Harvey got only 50,000 votes. The Liberty Party became only an exotic memory to most as the New Deal dance began.

The delegates nominated the aged Coin Harvey for the nation's highest office and then drifted back to their homes in 25 states. Remaining at Monte Ne, which was more than ever now one of the most publicized villages in the world, Harvey and his associates got busy pushing the campaign. Along with his secretary-wife and C. W. Henninger, party chairman, he settled down to some old-fashioned journalistic tom-tom beating in the pages of The Liberty Bell. This paper, mailed throughout the United States, became the Bible of the Harvey followers. The whole Liberty Party campaign was waged with the fervor of red-hot evangelism.

But in November the mass movement of voters to Governor Roosevelt's standard must have stamped a great many good Liberty Party people into the Democratic camp. Harvey got only 50,000 votes. The Liberty Party became only an exotic memory to most as the New Deal dance began.

Two campaign pins from the 1932 Liberty Party convention

William Hope Harvey was born in Buffalo, W. V., in 1851. Educated at Buffalo Academy and Marshall College in his home state, he became a school teacher at 16, an age when most boys were still digging fishworms. Before he was even old enough to vote he was quoting Blackstone as a member of the bar. He practiced in Cleveland and Chicago and while in the Windy City represented the millionaire Snell for a number of years before that wealthy Chicagoan was murdered. This experience must have strongly impressed young Harvey, for he carried a life-long mistrust of the effects of great wealth.

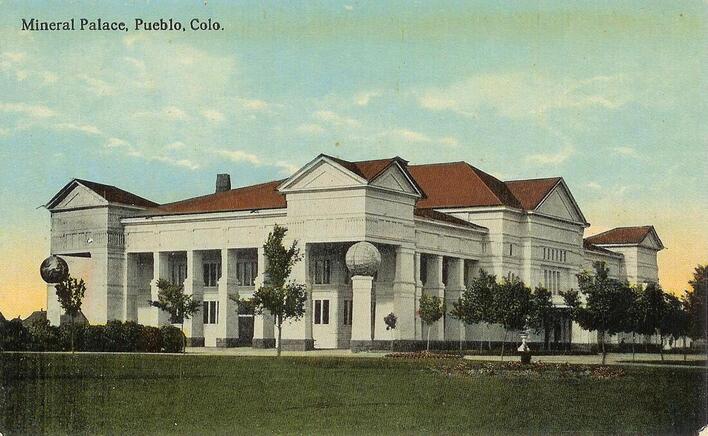

In 1884 Harvey was in Colorado, where he opened real estate offices in Denver and Pueblo. While living in the West he must have absorbed the sense of the spectacular which Westerners develop from living in a magnificent environment, for everything he was to attempt from this time was on the dramatic side. He became a sort of Cecil DeMille, minus the techicolor and shapely girls, of course. In 1899 he whipped together enough contributions to finance a great palace of minerals at Pueblo, where the products of Colorado's mines were dramatized in exciting exhibits. One exhibit was never forgotten by those who visited the hall. It was a gigantic statue of King Coal, carved by a Chicago sculptor from a solid piece of coal weighing 11,000 pounds. His fame as a promoter of spectacles reached Ogden, Ut., where he was invited to stage a Mardi Gras. He accepted and put on such a lively event that thousands of visitors swamped the city and were so impressed that many of them stayed as permanent residents.

In 1884 Harvey was in Colorado, where he opened real estate offices in Denver and Pueblo. While living in the West he must have absorbed the sense of the spectacular which Westerners develop from living in a magnificent environment, for everything he was to attempt from this time was on the dramatic side. He became a sort of Cecil DeMille, minus the techicolor and shapely girls, of course. In 1899 he whipped together enough contributions to finance a great palace of minerals at Pueblo, where the products of Colorado's mines were dramatized in exciting exhibits. One exhibit was never forgotten by those who visited the hall. It was a gigantic statue of King Coal, carved by a Chicago sculptor from a solid piece of coal weighing 11,000 pounds. His fame as a promoter of spectacles reached Ogden, Ut., where he was invited to stage a Mardi Gras. He accepted and put on such a lively event that thousands of visitors swamped the city and were so impressed that many of them stayed as permanent residents.

Image of the Mineral Palace Mr. Harvey help to build in Pueblo, Colorado

Harvey's restless energies took him back to Chicago in 1893. Always a lover of a good fight, he got in up to his neck in the struggle then raging over the free coinage of silver. He brought out a book called "Coin's Financial School," in which an eight-year-old boy named Coin completely routed the top financial wizards and economists of the day in a debate on the money question. Harvey used the youthful character to emphasize that even a school boy could understand that his (Harvey's) ideas on currency reform were sounder than the philosophy of capitalism at that time. The book caught on. A million copies were sold to set a world record in the publishing business. However seriously they took the ideas, people fought to get a copy as strenuously as their grandchildren were to fight to get "Forever Amber." In those days perhaps sex found sublimation in economics and politics. During the same year, Harvey wrote another best seller, "A Tale of Two Nations," It was a novel which pictured English money lords trying to wreck the American financial system by bribing dishonest congressmen into demonetizing silver and wrecking our international trade to the good of John Bull. One-half million copies of this great best seller were sold the first year.

Then came the hot campaign year of 1896, the year that saw William Jennings Bryan, nomimated by the Democrats, make the "cross of gold" speech which clinched him as the alltime Oscar-winner among convention orators. Harvey was Bryan's advisor and close friend as well as chairman of the party's Way and Means Committee. Bryan's defeat was upsetting to Harvey but he kept on pitching against gold until his own party snubbed him and decided to scuttle the money agitation once and for all. Harvey went into a rage and resigned his position. In fact, he decided to give United States civilization up as a bad deal and go live as a hermit in a remote place.

That is why Coin Harvey came to the Ozark mountains of Arkansas.

To be continued...

Then came the hot campaign year of 1896, the year that saw William Jennings Bryan, nomimated by the Democrats, make the "cross of gold" speech which clinched him as the alltime Oscar-winner among convention orators. Harvey was Bryan's advisor and close friend as well as chairman of the party's Way and Means Committee. Bryan's defeat was upsetting to Harvey but he kept on pitching against gold until his own party snubbed him and decided to scuttle the money agitation once and for all. Harvey went into a rage and resigned his position. In fact, he decided to give United States civilization up as a bad deal and go live as a hermit in a remote place.

That is why Coin Harvey came to the Ozark mountains of Arkansas.

To be continued...